Jason N. Johnson MD MHS1,2, Timothy D. Woods MD3, Benjamin R. Waller MD1

Institution: Division of Pediatric Cardiology1 and Pediatric Radiology2 LeBonheur Children’s Hospital and Division of Cardiology3, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, Tennessee

Clinical History:

A 64 year old female presented with a long history of vague dyspnea on exertion and intermittent palpitations. She had a history of mild exercise intolerance for the last 50 years with difficulty keeping up with her peers as early as high school. She had a normal physical exam with no murmur or gallop. A recent 24 hour Holter monitor was concerning for intermittent supraventricular tachycardia with possible atrial fibrillation. Her transthoracic echocardiogram showed left atrial dilation and concern for possible cor triatriatum with a membrane across the mid left atrium. A nuclear stress test was negative with no evidence of infarct or ischemia. She had a transesophageal echocardiogram that showed no evidence of cor triatriatum, severe left atrial dilation, dilated right coronary artery ostium, and continuous unidentified flow into the left atrium (Movie 1 and 2). A cardiac MRI and chest MRA was performed to evaluate the etiology of left atrial dilation in the setting of a dilated coronary artery.

Movie 1 and 2. Transesophageal echocardiogram, four chamber and color compare at 90 degrees revealing severe left atrial dilation, no cor triatriatum, and continuous unidentified color flow into the left atrium.

The cardiac MRI identified severe left atrial dilation, mild mitral valve insufficiency, and normal bi-ventricular size and systolic function (Movie 3 and Table 1).

Table 1. Left atrial and ventricular volumes, aortic valve flow, and coronary artery fistula flow. | ||

Absolute | Indexed to BSA | |

Left Atrial End-Systolic Volume | 197 ml | 94 ml/m2 |

Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume | 148 ml | 72 ml/m2 |

Left Ventricular End-Systolic Volume | 54 ml | 26 ml/m2 |

Left Ventricle Stroke Volume | 94 ml | |

Aortic Valve Flow | 92 ml/beat | |

Coronary Artery Fistula Flow | 10 ml/beat | |

Movie 3. Cine SSFP four chamber illustrating the severe left atrial dilation, mild mitral valve insufficiency, and normal bi-ventricular size and systolic function.

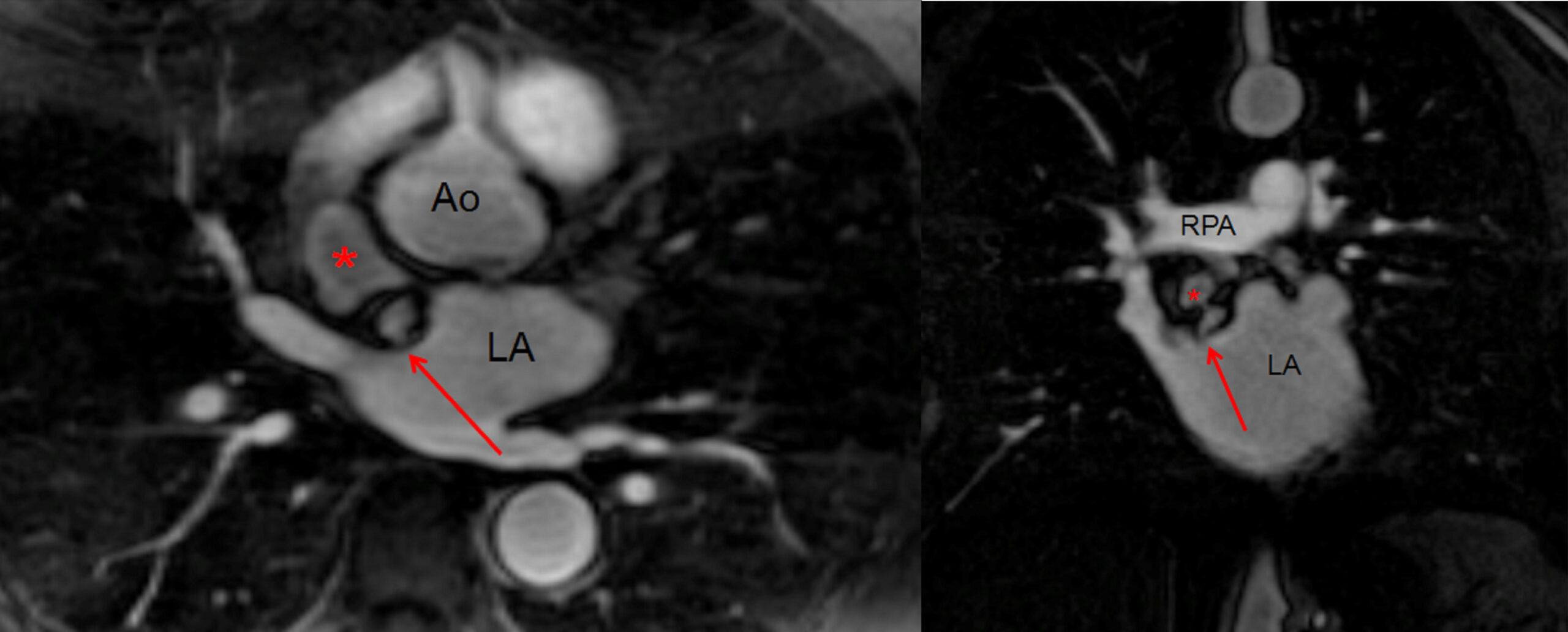

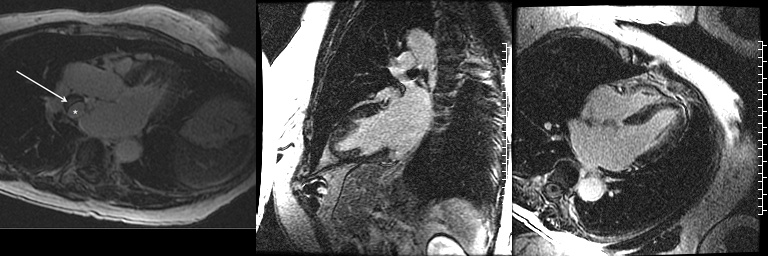

A large aneurysmal coronary artery fistula from the right coronary artery to the left atrium was identified. The coronary fistula coursed rightward, posteriorly, and superiorly before entering into the left atrium near the right upper pulmonary vein

(Movie 4-6 and Image 1-3).

Movie 4-5. Coronal contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography and axial range illustrating a coronary fistula with three separate aneurysmal segments arising from the right coronary artery coursing rightward, posteriorly, and superiorly before entering into the left atrium near the right upper pulmonary vein.

Image 1-2. Still images of the 3D MRA in the axial and coronal plane at the same level showing the coronary artery fistula aneurysm (red *) and entrance of the fistula into the left atrium (red arrow) near the right upper pulmonary vein entrance. Ao = Aorta. LA = Left Atrium. RPA = Right Pulmonary Artery.

Movie 6 and Image 3. Cine SSFP off-axis sagittal projection illustrating the coronary artery fistula (white arrow), aneurysmal segments (white *), and entrance into the left atrium (red arrow).

There were three separate large aneurysmal segments of the fistula with the largest measuring 3.1 x 2.1 x 2.0 cm (Movie 7 and Image 4).

Movie 7 and Image 4. Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography with 3D reconstruction with horizontal rotation highlighting the coronary artery fistula (white and black arrows) and large aneurysmal segments (black *). AA = Ascending Aorta. DA = Descending Aorta. LA = Left Atrium.

There was no evidence of thrombus in the atria, but there was concern for possible mural thrombus versus calcification in one of the aneurysmal segments of the coronary artery fistula (Image 5). There was no myocardial late gadolinium enhancement (Images 5-7).

Image 5-7. Late gadolinium delayed enhancement in the left ventricular outflow tract, two chamber left, and four chamber views demonstrating no myocardial late gadolinium enhancement. The left ventricular outflow tract view shows the hypointense wall (white arrow) of the aneurysmal segment (white *) of the coronary fistula concerning for possible mural thrombus versus calcification.

By phase contrast imaging, 10% of the left ventricular stroke volume coursed through the coronary artery fistula (Movie 8 and Image 8). The percentage of blood flow through the fistula compared to the left ventricular stroke volume was calculated by the formula, coronary artery fistula flow / left ventricular stroke volume x 100 (Table 1).

Movie 8 and Image 8. Phase contrast imaging cine and still frame of the coronary artery fistula en face (red arrow) illustrating continuous flow throughout systole and diastole. Tracing of the coronary artery fistula (red circle) was performed in each frame to calculate the flow through the fistula.

Conclusion:

The diagnosis of a large aneurysmal coronary artery fistula from the right coronary artery to the left atrium was made after the cardiac MRI. The patient’s symptoms, severe left atrial dilation, and evidence of a significant portion of cardiac output coursing through the fistula supported closure. The MRI showed the coronary artery fistula extended 3 cm from the right coronary artery to the first aneurysmal segment, and made an ideal landing zone for coil occlusion. Therefore, the patient had successful transcatheter coil occlusion of the right coronary artery fistula proximal to the aneurysmal segments (Movie 9). The patient developed atrial fibrillation hours after the coil occlusion, and she was placed on dronedarone and apixaban until a successful ablation was performed a few weeks later. She is currently off antiarrhythmic medication with improvement in her dyspnea on exertion and palpitations.

Movie 9. Coronary artery angiogram after coil occlusion of the coronary artery fistula.

Perspective:

Coronary artery fistulas are defined as a direct communication between any coronary artery and any cardiac chamber or adjacent vessel [1]. Coronary artery fistulas are quite rare being found in only 0.1% of coronary artery angiography and 1 in 50,000 patients with congenital heart disease [1,2]. The fistulas arise more commonly from the left coronary system compared to the right, and typically drain into right cardiac chambers compared to the left [3]. We believe this is the first report of a coronary artery fistula arising from the right coronary artery with large aneurysmal segments draining to the left atrium. Only six previous documented cases have drained into the left atrium, all originating from the left coronary artery system [1,3-6]. Large aneurysms associated with coronary artery fistulas are rare as well occurring in only 6% of patients with coronary artery fistula [5]. Coronary artery fistulas typically are asymptomatic during childhood, and symptoms like fatigue, dyspnea, or congestive heart failure do not present until adulthood [3]. Diagnosis of a coronary artery fistula can be made by echocardiogram, computed tomography angiography (CTA), cardiac MRI, and catheterization. Cardiac MRI and ECG gated CTA are accurate, noninvasive imaging techniques for the detection of coronary artery fistulas. ECG gated CTA acquires high resolution, 3D datasets quickly at the expense of ionizing radiation [7]. Cardiac MRI also acquires 3D datasets with added functional assessment (atrial and ventricular volumes and flow assessment) that does not utilize ionizing radiation [7]. Therefore, we chose the cardiac MRI to identify the course and size of the coronary artery fistula and aneurysmal segments, and to evaluate the functional assessment of the flow through the fistula without radiation.

There is no consensus statement regarding closure of coronary artery fistulas [8]. Small coronary artery fistulas without aneurysmal segments in an asymptomatic patient likely should not be closed as spontaneous resolution of coronary artery fistulas has been documented [8]. We felt this patient met several indications for closure as she was symptomatic, had severe left atrial dilation, and had large aneurysmal segments of the fistula [1-6]. Transcatheter closure of coronary artery fistulas has been well described and appears to be comparable with surgical closure in rates of successful closure and early and late complications [4]. Multiple techniques for surgical repair of coronary artery fistula have been described with and without coronary artery bypass with excellent success rates [1,3,5,6]. Transcatheter occlusion of a coronary artery fistula should be considered in the following conditions: ability to safely cannulate the coronary artery that supplies the fistula, absence of large branch vessels that could become embolized, presence of a restricted drainage site, and absence of multiple fistulous connections [1].

Click here to view case on Cloud CMR

Click here to view 3D reconstructions on Cloud CMR

REFERENCES:

2. Vavuranakis M, Bush CA, Boudoulas H. Coronary artery fistulas in adults: Incidence, angiographic characteristics, natural history. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995;35(2):116-120.

3. Kamiya H, Yasuda T, Nagamine H, Sakakibara N, Nishida S, Kawasuji M, Watanabe G. Surgical treatment of congenital coronary artery fistulas: 27 years’ experience and a review of the literature. J Card Surg. 2002;17:173-177.

4. Armsby LR, Keane JF, Sherwood MC, Forbess JM, Perry SB, Lock JE. Management of coronary artery fistulae: Patient selection and results of transcatheter closure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1026-1032.

5. Li D, Wu Q, Sun L, Song Y, Wang W, Pan S, Luo G, Liu Y, Qi Z, Tao T, Sun JZ, Hu S. Surgical treatment of giant coronary artery aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;130:817-821.

6. Mawatari T, Koshino T, Morishita K, Komatsu K, Abe T. Successful surgical treatment of giant coronary artery aneurysm with fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1394-1397.

7. Zenooz NA, Habibi R, Mammen L, Finn JP, Gilkeson RC. Coronary artery fistulas: CT findings. Radiographics. 2009;29:781-789.