Fateh Ali Tipoo Sultan1, Babar Hasan1, Vincent L. Sorrell2, Arash Seratnahaei2

1Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

2 University of Kentucky Medical Center, Gill Heart Institute, Lexington, KY

Clinical History

A 19 year old male with no previous cardiovascular history presented with NYHA Class III heart failure symptoms. Electrocardiogram on presentation showed normal sinus rhythm with Himalayan P waves (P waves > 5 mm and peaked in lead II), right bundle branch block and right axis deviation.

Figure 1. ECG: Normal sinus rhythm with Himalayan P waves, right bundle branch block, and right axis deviation.

The patient underwent an echocardiogram which reported severe right atrial (RA) and right ventricular (RV) dilation with a pathologically thin RV wall as well as normal tricuspid valve position. The findings were not consistent with Ebstein’s anomaly. Due to his abnormal electrocardiogram and echocardiographic findings, a cardiac MRI (CMR) was obtained for comprehensive RV & left ventricular (LV) quantification, exclusion of cardiac shunt, and myocardial tissue characterization.

CMR Findings

A Siemens Avanto 1.5T scanner was employed to obtain imaging sequences which included cine with SSPF, T1 weighted dark blood imaging and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging.

CMR confirmed the severely dilated RA and RV (RVEDV= 950 mL, indexed RVEDV= 633 mL/m2) with a pathologically thin (essentially unseen) RV myocardial wall. The tricuspid valve was indeed normally positioned and there was severely reduced biventricular systolic function (RVEF 7%, LVEF 20%) (Movies 1, 2, 3 and 4). Tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR) was severe with a regurgitant fraction of 57%. The TR was thought to be secondary to annular dilation and not the primary etiology for the RV pathology. T-1 weighted and LGE images showed no hyperintense signal to suggest fibrofatty infiltration of the RV or LV (Figures 2 and 3). There appeared to be evidence of LGE along the distal free wall and apical RV wall as well as the RV portion of the distal ventricular septum. This finding has not been previously reported and since we do not have any pathologic correlation, our discussion that follows is based upon our review of the relatively scant published literature.

Movie 1: Four-chamber SSFP cine demonstrating a dilated RA, and a RV with a thin wall and normally positioned tricuspid valve. Biventricular systolic dysfunction was present.

Movie 2: RA-RV SSFP cine showing a dilated RA and thin walled RV.

Movie 3: RVOT SSFP cine showing a dilated RV and thin RV wall.

Movie 4: Short axis SSFP cine confirming biventricular systolic dysfunction and showing interventricular septal wall flattening during diastole.

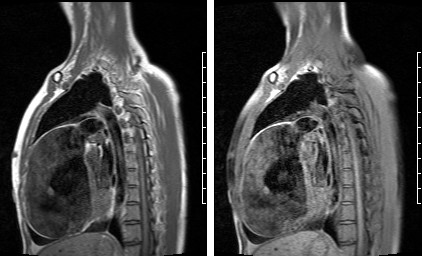

Figure 2: RVOT turbo spin echo T1 weighted (a) and with fat saturation pulse sequence (b) showing no evidence of fibrofatty RV wall infiltration.

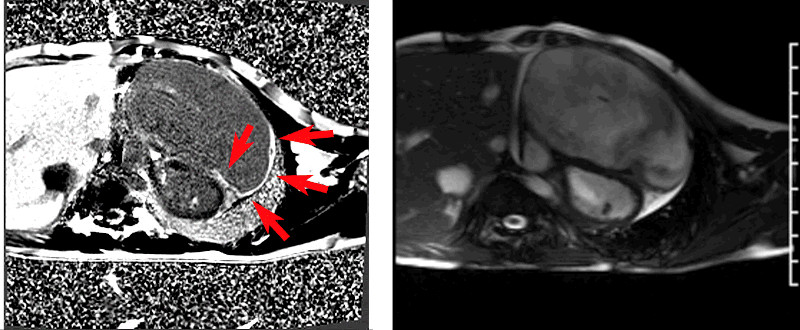

Figures 3a and 3b: Short axis LGE images showing enhancement (arrows) along the distal free wall and apical RV wall as well as the RV portion of the distal ventricular septum with a small amount of pericardial effusion. There was no LV wall LGE. Corresponding short axis SSFP cine still (3b) in diastole.

Conclusion

These findings were consistent with Uhl’s anomaly. The patient was treated with optimal medical therapy while awaiting cardiac transplantation evaluation, but sadly, he died of progressive heart failure before workup was completed. There were no reported ventricular arrhythmias. Since this was not considered a medicolegal case, an autopsy was not performed.

Perspective

Uhl’s anomaly is a rare congenital condition in which the RV myocardium is absent. Instead there is juxtaposition of the epicardium and endocardium and thus has a parchment-like appearance with associated RV systolic dysfunction (1). Selective apoptosis of the RV myocytes is the postulated mechanism (2,3). An important distinction must be made from arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) which is characterized by fibrofatty infiltration of the RV wall (4). While echocardiography is useful in suggesting the diagnosis of Uhl’s anomaly, CMR with the use of various methods for myocardial tissue characterization as described above can confirm the diagnosis noninvasively.

There are very few multimodality imaging reports on Uhl’s anomaly and therefore, this report was considered important. Furthermore, there are no reports of LGE, so whether or not this case example represents a common or rare phenomenon is unknown. Our hypothesis that this represents regional fibrosis from the progressive RV myocardial apoptosis is based in part upon the pattern noted in the ventricular septum. The LGE seems to extend along the distal RV side of the septum implying that this is indeed tracking the normally distributed RV myocardial contribution to this ventricular anatomic divide. There are reports of ‘partial’ Uhl’s and maybe the LGE is evidence of different degrees of apoptosis and duration of disease in the adult patient.

Another potential unique aspect of this patient’s case is the marked LV systolic dysfunction. Review of the available literature shows that the LV systolic function is frequently reported as normal or not reported at all. However, there are scant reports of depressed LV systolic function. Therefore, the true incidence of LV systolic dysfunction is unknown, and we theorize the presence or extent of LV systolic dysfunction could be a sign of end-stage disease process and could be a result of abnormal LV mechanics due to RV volume overload in this particular example. Another example of LV dysfunction can be a result of advanced RV pressure overload. Most of us in the CMR community have seen examples of ARVD that included severe RV dilation and dysfunction. Some of these severe cases will involve the LV and result in a biventricular dilation and dysfunction. However, this case is distinguished from that entity by its nearly complete absence of papillary muscles or RV trabeculations.

This case also underscores the collaborative effort between our institutions (University of Kentucky Medical Center, Gill Heart Institute and Aga Khan University Hospital in Pakistan) to bring rare anomalies to a wide audience not only from different institutions but also from different regions of the world. This patient case marks the second of such efforts between our institutions (5).

Click here to view all CMR images for the case on CloudCMR

References

1. Uhl HSM. A previously undescribed congenital malformation of the heart: almost total absence of the myocardium of the right ventricle. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1952;91:197–205.

2. Uhl HSM. Uhl’s anomaly revisited. Circulation. 1996;93:1483–1484.

3. James T, Nichols M, Sapire D, et al. Complete heart block and fatal right ventricular failure in an infant. Circulation. 1996;93:1588 –1600.

4. Gerlis L, Schmidt-Ott SC, Ho S, et al. Dysplastic conditions of the right ventricular myocardium: Uhl’s anomaly v arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Br Heart J. 1993;69:142–150.

5. Sultan F, George B, Ahmed I, Sorrell V. Cardiac involvement of cystic echinococcosis by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. http://scmr.site-ym.com/?page=COW1514. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) website

Case prepared by Associate Editor: Adrian Dyer