Case from: Madhusudan Ganigara, Stephen G Cooper, Richard B Chard, Rajesh Puranik, Julian G Ayer.

Institute: The Heart Centre for Children, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Australia

Clinical history:

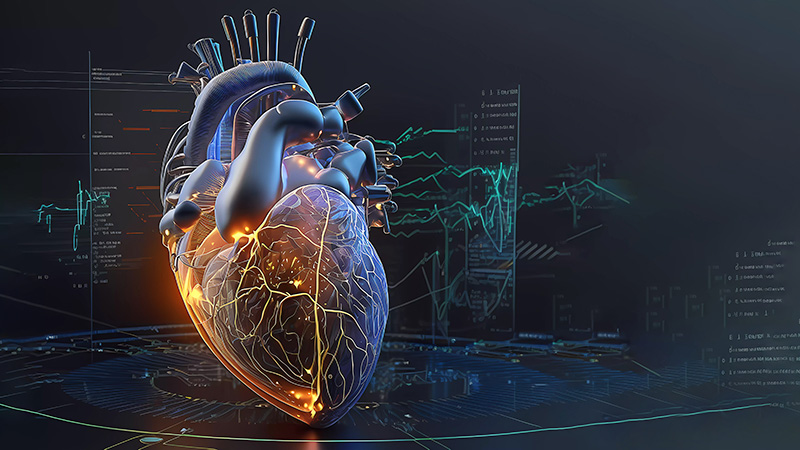

A 15-year-old boy presented with progressively worsening exertional dyspnea following balloon aortic valvotomy in infancy for congenital aortic stenosis. Clinical and echocardiographic evaluation revealed severe aortic stenosis and moderate aortic regurgitation. He underwent the Ross procedure – aortic root replacement with a pulmonary autograft and pulmonary valve replacement with a 22 mm aortic homograft.

After an uneventful early post-operative period, he developed recurrent pericarditis with pericardial effusion beginning in the first few months after surgery. This was associated with fever and chest pain. Although, therapy with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colchicine was unsuccessful, the pericarditis improved with systemic steroids and Azathioprine.

At one-year follow up post-Ross procedure, a transthoracic echocardiogram showed a well functioning neo-aortic valve with normal ventricular function. There was a large aneurysm of the homograft in the pulmonary position measuring approximately 5 x 6 cm. There was diastolic flow reversal in the branch pulmonary arteries, suggesting regurgitation from the branches and distal homograft into the aneurysm.

Video 1: Transthoracic echocardiogram in parasternal short axis view showing the aneurysmal pulmonary homograft (anterior-most structure).

Video 2 : Transthoracic colour Doppler echocardiogram in parasternal short axis view showing the aneurysmal pulmonary homograft (anterior-most structure) with the regurgitant pulmonary blood flow.

CMR Findings: Cardiac MRI (CMR) was performed to better visualise the aneurysm and to define its relationship to the branch pulmonary arteries and the sternum. This showed a well functioning neo-aortic valve. There was a very large aneurysm measuring approximately 5×7 cm, arising from the proximal part of the pulmonary homograft and extending to the distal end of the homograft. The distal homograft and the branch pulmonary arteries were unobstructed. Abnormal swirling flow was noted within the aneurysm. Flow measurements (Table 1) suggested moderate to severe incompetence of the homograft. Both the ventricles were normal sized with normal function. The coronary arteries were not distorted and were remote from the aneurysm.

Video 3 : Cine MRI of the 4-chamber view

Video 4 : Cine MRI of the left ventricular long axis view

Video 5 : Cine MRI of the axial stack through the thorax

Table 1 : Flow data obtained using phase contrast imaging

The patient underwent redo-sternotomy with take-down of the homograft and replacement of the pulmonary valve using a 27 mm bio-prosthesis. Histopathological examination of the explanted aortic homograft did not show evidence of significant active inflammation. On follow up at 6 months post-operatively he was asymptomatic with satisfactory function of both the neo-pulmonary valve and neo-aortic vale. All immunosuppression was ceased a few months post surgery.

Conclusion:

Pulmonary autograft replacement of the aortic valve (Ross Procedure) is an option in children and adolescents with aortic valve disease. Cryopreserved homografts, initially introduced in 1966 by Ross and Somerville [1], have become the most commonly used valved conduit for reconstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). They have the advantages of technical ease of implantation and improved hemostasis.

Although results are better compared to other forms of reconstruction of the RVOT, homograft dysfunction is the commonest reason for reoperation. The average incidence of structural and non-structural dysfunction of right ventricle to pulmonary artery homografts in children is 1.6 (range 0.7–4.9) per 100 patient-years [2]. One of the proposed mechanisms of homograft dysfunction is that it represents a form of ‘rejection’ and related low-grade chronic inflammation [3]. We might speculate that in the present case, post-operative inflammation produced both recurrent pericarditis, and homograft dysfunction and aneurysm formation. Lack of histopathological evidence of inflammation is presumably a result of ongoing immunosuppression and/or burnt-out chronic inflammation.

The commonest reason for explanting the homograft after the Ross procedure is conduit stenosis [4]. Aneurysmal dilatation of the homograft is a rare occurrence with limited reports in literature. Imaging to assess the dimension and the extent of dilatation, and associated valvar or branch pulmonary artery stenosis is challenging when using transthoracic echocardiography alone. CMR overcomes the limitations of acoustic windows in echocardiography with good anatomic profiling and also provides additional functional and physiological information.

The present case highlights an important and unusual complication of the homograft reconstruction of the RVOT. Multi-modality imaging including CMR showed the extent and size of the aneurysm. This improved the surgical planning and thus the outcome.

Perspective:

This case demonstrates the unusual complication of aneurysm formation within a homograft in the pulmonary position, in the context of a refractory systemic inflammatory syndrome where high high-dose immunosuppressive therapy was required for prolonged periods. This raises the possible association between conduit dysfunction and pathological immunological response. Furthermore, CMR is an excellent imaging modality that provides valuable anatomical and functional information that aids surgical planning.

References:

COTW handling editor: Madhusudan Ganigara, MD