Case from: G Cooper, R Shifrin, T Lee, B Silverstein and J Peteresen

Institute: University of Florida, Cardiac Imaging Service, Florida, USA

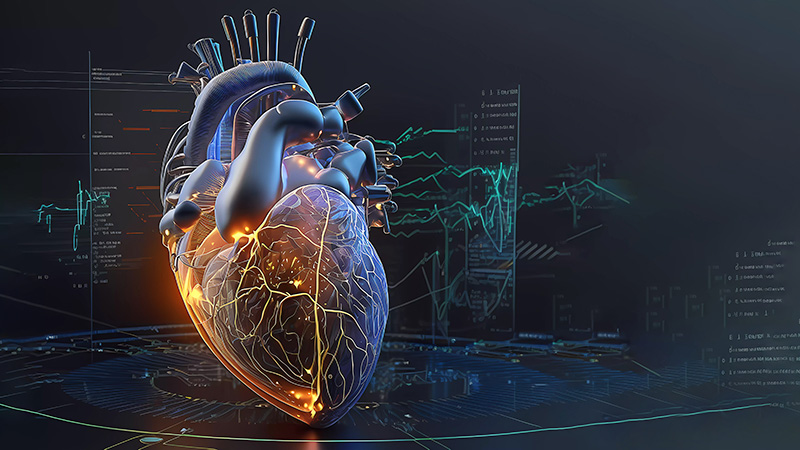

Introduction: Myocardial contusion is a ubiquitous cause of hospitalization. The most common etiologies (1) are auto-pedestrian accident, CPR, fall from heights>20′, and motor vehicle accidents. The majority of patients will have a troponin leak and may have ECG changes. Since the right ventricle is the most anterior portion of the heart it is commonly traumatized. Most patients survive and are discharged without complication. But, any chamber or valve can be affected. There are infrequent long term consequences.

Pathologically, there is cellular damage that arises from non-penetrating chest trauma. This is characterized by patchy areas of muscle necrosis and hemorrhage with local infiltration.

The following cases represent examples of long term sequelae of blunt closed chest cardiac trauma.

Clinical Case Number 1.

A 34 year-old white male is seen in consultation for elective surgery because of an asymptomatic heart murmur. He reported a “heart bruise” 17 years ago from an unrestrained motor vehicle accident. On clinical examination, his vital signs were normal. He was acyanotic, without clubbing. A right ventricular lift, a 2/6 holo-systolic murmur at the left sternal border and an RV S3 were present.

Trans-thoracic echo (not shown) revealed normal LV function, marked right ventricular dilation, marked right atrial dilation, severe tricuspid regurgitation and a possible fenestrated ASD.

Right & left heart cathetrization confirmed an LVEF of 55%, severe tricuspid regurgitation, severe RV dilatation, severe RA dilation, and normal coronary arteries. RA: A-19, V-19, mean-10 mm Hg; RV: 22/6 Mean-11; PA18/8 Mean 9; PAC: Mean 9; LV 130/5 LVEDP-22; Ao 130/70 mean 99 mmHg.

He was referred for CMR to determine the etiology of his tricuspid regurgitation.

MOVIE 1 SSFP high temporal resolution, 4-chamber cine. Severe tricuspid regurgitation, mild mitral regurgitation severe RV dilatation, marked right atrial dilatation. Possible small ASD

MOVIE 2 SSFP short axis cine, basal slice. Marked dilatation of the inferior vena cava. Minimal diastolic flow from the mid left atrium to the mid right atrium.

MOVIE 3 SSFP short axis cine, mid-cavity slice. Marked RV dilatation with associated septal “bounce”

MOVIE 4 SSFP RV in and out flow tract cine. Severe tricuspid regurgitation.

CMR Findings: Global RV Function: RV ejection fraction = 46.6 %, RV end diastolic volume = 476.6 cc, RV stroke volume = 117.0 cc .

Global LV Function: LV ejection fraction = 51.6 %, LV end diastolic volume = 73.6 cc, LV stroke volume = 38.0 cc, LV myocardial mass = 83.6 gms .

Qp:Qs=1.0

TAPSE (Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion) = 3.5 cm. [Normal >1.8 cm]

CMR Final Impressions for Case 1: There is no evidence of Ebstein’s anomaly, “burned out” ARVC (Stage 4), Uhl’s anomaly, ventricular septal defect, pulmonic stenosis, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis or other forms of serious congenital heart disease. There may be a small intra-atrial communication. There is no significant intra cardiac shunt. The severe tricuspid regurgitation is likely a consequence of the patient’s history of myocardial contusion 17 years ago.

Findings at Surgery: “The posterior leaflet as well as a portion of the septal leaflet was completely dehisced. There was severe tricuspid regurgitation with no valvular competence whatsoever. A 33-mm porcine valve was chosen for tricuspid implantation.”

Clinical Case Number 2.

A 32 year old white male was involved in an motor vehicle accident. He was a restrained driver. Initial troponin on admission was <0.03, total CK was 4951, and CK-MB was 5.9.

Movie 5

Trans-thoracic echo showed left apical dyskinesis and a left ventricular mass (Movie 5)

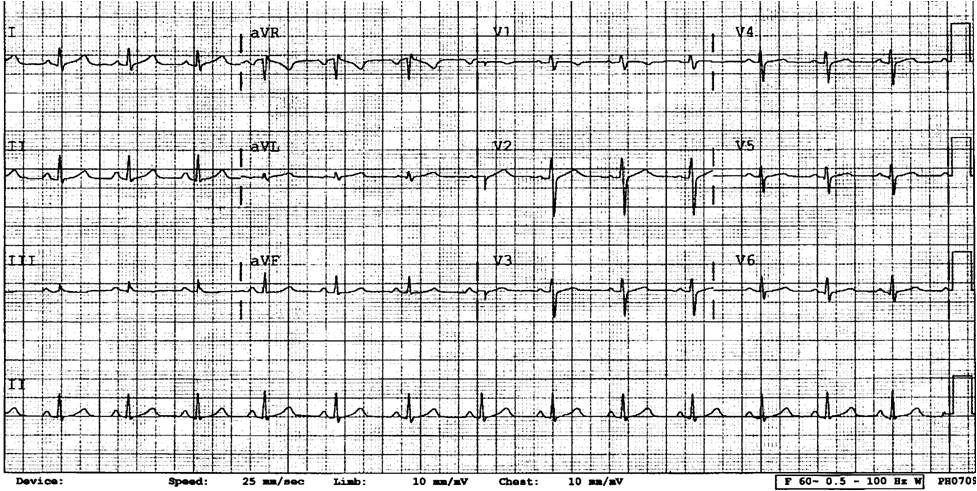

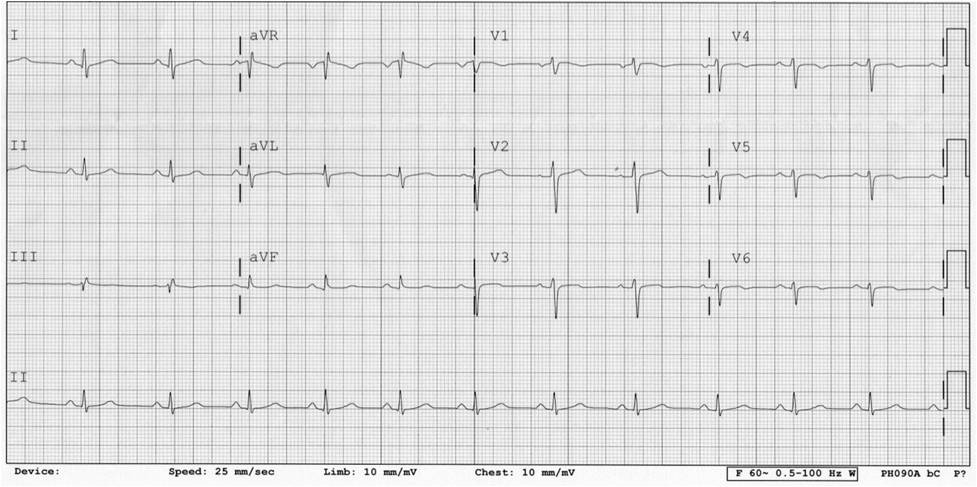

Figure 1 – ECG on admission.

ECG on initial admission was normal (Figure 1).

Movie 6 & Movie 7

Movie 8

Because of the apical dyskinesis and persistent chest pain, the patient underwent left heart cathetrization and coronary angiography [Movies 6,7,8] which confirmed the apical wall motion abnormality and the absence of significant epicardial coronary artery disease. The apical mass was confirmed.

The patient received a year of Coumadin therapy. Serial trans-thoracic echos showed resolution of the LV apical filling defect. At the patient’s insistence his anticoagulation was stopped.

Two years later he presented with headache in the left parietal area, aphasia and right upper extremity weakness and numbness. His motor deficits resolved after 15 minutes but speech problems persisted for a day. Repeat trans-thoracic echo once again showed an apical left ventricualr mass associated with apical dyskinesis.

Figure 2 – ECG two years later.

ECG two years later (Figure 2), at the time of the neurological episode, showed normal sinus sythm, slow R wave progression anteriorly and new T wave abnormalities.

CMR was ordered to better characterize the LV apical wall motion abnormality and apical LV mass.

CMR Findings:

Movie 9

SSFP 2- and 4-chamber cine. Thin and dyskinetic LV apex with a large apical mass

Movie 10

SSFP Short-axis cine stack.The mid and basal segments have normal contractility.The apex is dyskinetic and contains a mass

Movie 11

Mid-ventricular level perfusion cine shows normal myocardial perfusion. The mass does not perfuse.

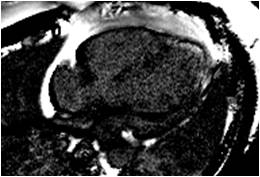

Figure 3

Figure 4

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the modul

Early (Figure 3) and late gadolinium enhancement (Figure 4 – PSIR sequence) images confirm that the apical LV mass is a large apical thrombus in the setting of apical dyskinesia associated with apical scarring.

Perspective: CMR complements other non-invasive and invasive studies in characterizing the short and long term consequences of myocardial contusion. With CMR’s wide field of view, ability to characterize tissue, flow quantification, visualization of the great vessels, wall motion and valve functionality evaluation, CMR is indicated in the assessment of complicated cases of closed chest cardiac injury (2).

References:

(1) Blunt Trauma to the Heart and Great Vessels. Pretre R, Chilcott M. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:626-632.

(2) Cardiac Injuries in Blunt Chest Trauma. Huguet M, Tobon-Gomez C, Bijnens BH, Frangi AF, Petit M. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2009, 11:35.

COTW handling editor: Monica Deac

Have your say: What do you think? Latest posts on this topic from the forum

e Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.