Case from: Elisabetta Chiodi1, Donato Mele2, Andrea Fiorencis3

Institute: Departments of Radiology1 and Cardiology2, S.Anna Hospital Ferrara, University of Ferrara3

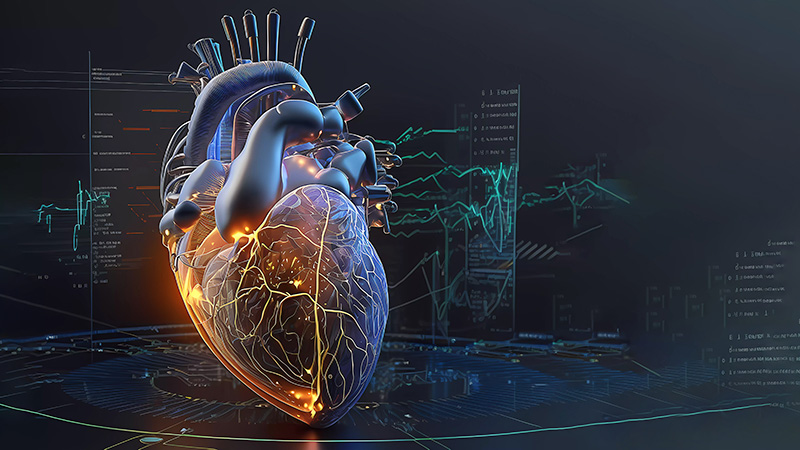

Clinical history: 68 year old female, smoker, with a history of hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. In 2007 she suffered from a myocardial infarction with incomplete revascularization due to ineffective primary angioplasty. In 2009 an echocardiogram documented a left ventricular apical aneurysm and systolic dysfunction (25% ejection fraction). The patient refused an ICD at that time. In February 2010 she reconsidered the ICD as she represented with severe dyspnea.

Her presenting ECG demonstrated a sinus tachycardia of 120 bpm and a wide QRS consistent was a left bundle branch block.

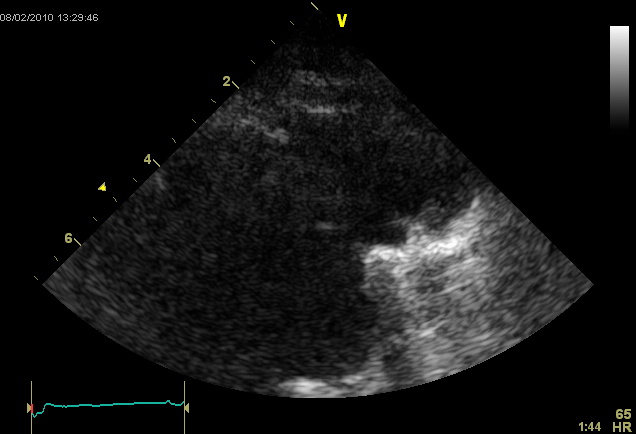

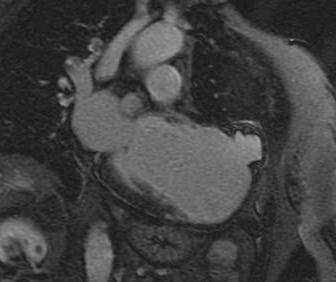

An echocardiogram was performed (Movie 1) which demonstrated a severely dilated left ventricle with diffuse contractile dysfunction, 15% ejection fraction, and an unclear geometric distortion of the aneurysmal apex (Image 1).

Movie 1: Echocardiogram, apical four chamber

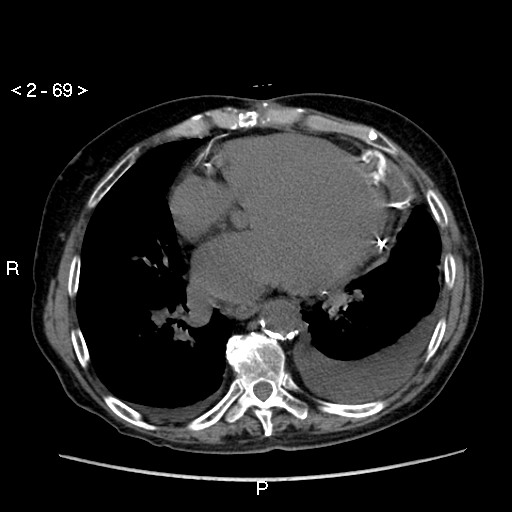

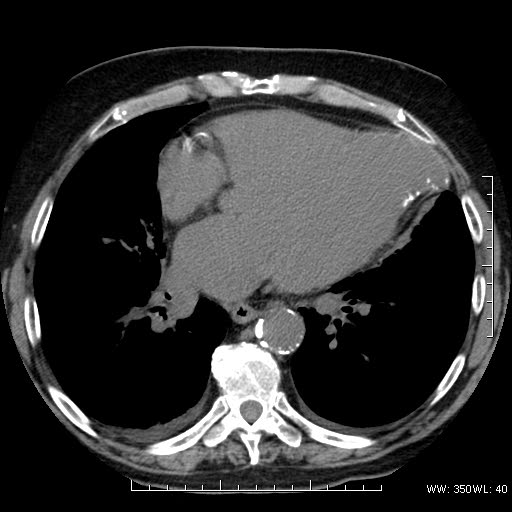

A noncontrasted gated cardiac CT was performed to further define the apical abnormality (Images 2 & 3). The CT demonstrated a large disruption of the left ventricular apex with evidence of calcification near the collar of the defect. There was also marked aortic calcification and bilateral pleural effusions.

Image 2: Chest CT demonstrating a contained rupture of the LV apex with associated calcifcations

Image 3: Chest CT demonstrating the LV apical defect with a wide collar and calcification

A Cardiac MRI (GE Twinspeed 1.5 T) was performed to further identify the possibility of concommitant LV aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm. Steady state free precession CINE MRI demonstrated severe left ventricular dysfunction, left ventricular apical remodeling with a 22 mm collar, and thrombotic stratification (Movie 2).

Movie 2: Cardiac MRI, short axis CINE stack

Delayed enhancement images demonstrated scar of the apex. There was evidence of rupture of the aneurysmal wall with containment by a thin layer of parietal pericardium.

Figure 4: Delayed enhancement, pseudoaneurysm

Figure 5: Delayed enhancement, thrombus within the aneurysmal sac

Perspective: Aneurysms typically occur due to myocardial infarction and scar. True aneurysms are bulges of myocardial tissue in areas of necrotic myocardium without disruption of the visceral pericardium. Pseudoaneurysms occur when a myocardial rupture occurs and is contained by parietal pericardium and fibrous tissue. Despite this containment, pseudoaneurysms have a high risk of rupture. Clinical presentation includes congestive heart failure (36%), chest pain (30%) and dyspnea (25%), while the incidence of sudden death at the onset is 3%.

Echocardiography is a valuable non-invasive tool for diagnosing aneurysms. However, in cases of inadequate image quality CMR is needed for final diagnosis. The advantage of CMR is includes a high resolution evaluation of the myocardium, pericardium, and thrombi. Visualization of epicardial fat layer disruption at the site of the pseudoaneurysm is also possible. Additionally, this technique is highly accurate in determining the size and location of this abnormality for surgical planning.

The originality of this case is the simultaneous presence of both lesions, the true and pseudo-aneurysm, recognized by CMR. There are qualities present for true aneurysm (wide collar, delayed enhancement within the sac, chronicity of defect) and pseudoaneurysm (disruption of myocardium, thrombus within the pericardial space, involvement of the parietal pericardium). Because early diagnosis is essential to determine the appropriate lesion treatment, CMR has played a decisive role in this case.

References:

- Brown SL, Gropler RJ, Harris KM. Distinguishing left ventricular aneurysm from pseudoaneurysm. A review of the literature. Chest 1997;111: 1403-9.

- Frances C, Romero A, Grady D. Left Ventricular Pseudoaneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:557-61.

- Contuzzi R, Gatto L, Patti G, Goffredo C, D’Ambrosio A, Covino E, Chello M, Di Sciascio G. Giant left ventricular pseudoaneurysm complicating an acute myocardial infarction in patient with previous cardiac surgery: a case report. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10:81-84.

- Konen E, Merchant N, Gutierrez C, Provost Y, Mickleborough L, Paul NS, Butany J. True versus false left ventricular aneurysm: differentiation with MR Imaging–initial experience. Radiology 2005;236:65-70.

- Davutoglu V, Soydinc S, Sezen Y, Aksoy M. Unruptured giant left ventricular pseudoaneurysm complicating silent myocardial infarction in a diabetic young adult. Int J CV Imaging. 2005; 21: 231-234.

COTW handling editor: Kevin Steel