Case from: Alma O. Iacob1*, Thomas J. Cahill1, Margaret Loudon2, Theodoros Karamitsos3, Susan J. Davies4 and Attila Kardos1

Institute: 1 Department of Cardiology, Milton Keynes NHS Hospital Foundation Trust, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom; 2 Department of Cardiology, Oxford University Hospitals, Oxford, United Kingdom; 3 Honorary Consultant in Cardiovascular Imaging. Oxford Centre for Cardiac Magnetic Reseonance. Oxford, United Kingdom; 4 Department of Cellular Pathology, Oxford University Hospitals, Oxford, United Kingdom

Clinical history:

A 58 year-old man was admitted to hospital with a short history of rapidly progressive breathlessness, haemoptysis, weight loss and fatigue. There was no past medical history and he took no regular medication. On examination he was tachypnoeic and tachycardic but normotensive, with a jugular venous pressure elevated at 8cm and muffled heart sounds. The chest was clear and there was no peripheral oedema.

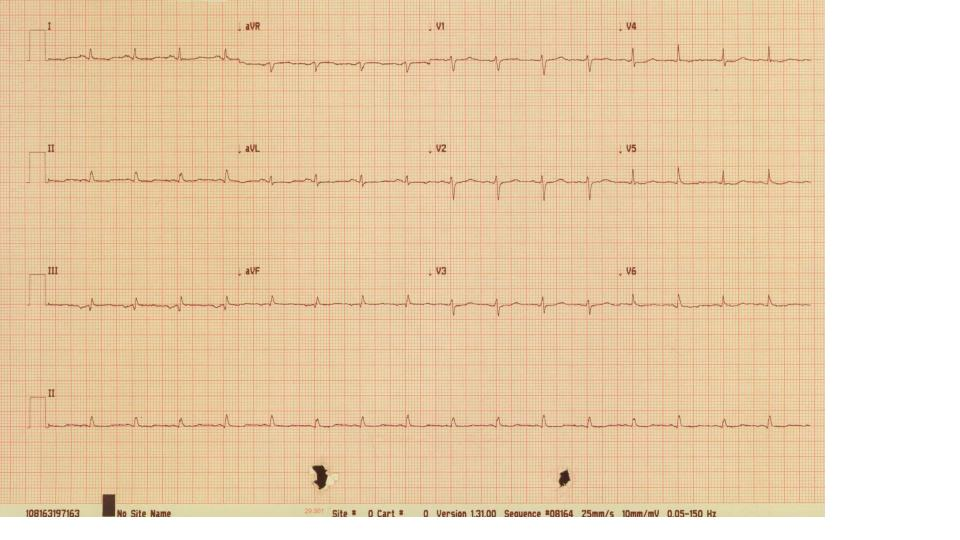

His electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with small voltage QRS complexes and a degree of electrical alternans (Fig 1).

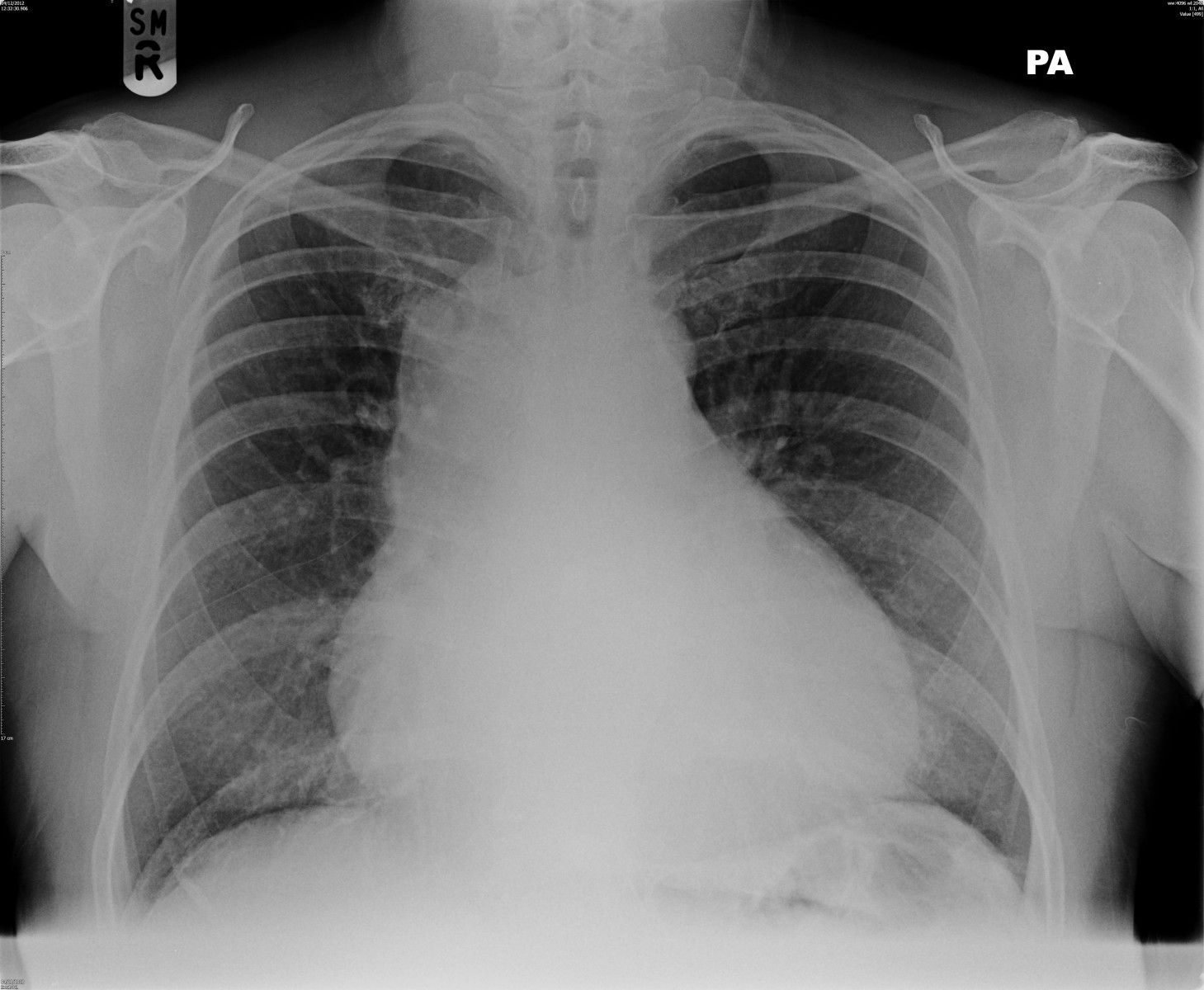

A chest X-ray demonstrated widening of the mediastinum and cardiomegaly (Fig.2).

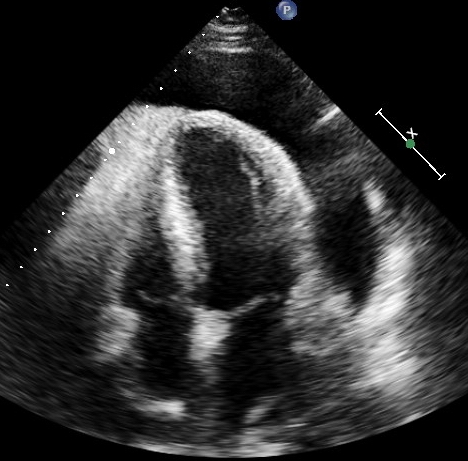

A subsequent echocardiogram confirmed a large (4 cm) circumferential pericardial effusion with no evidence of tamponade physiology; a four chamber echocardiographic view revealed a thick echogenic epicardial layer (Fig.3).

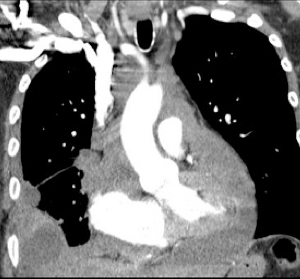

Fig 4. Axial section from the CT chest showing the large circumferential pericardial effusion.

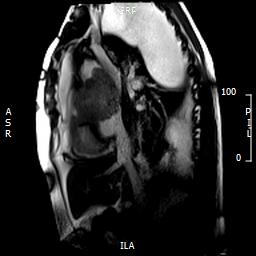

Fig 5. Sagittal section showing SVC insertion into the right atrium and extensive pericardial effusion.

In addition, there was no mass reported on an initial CT chest (Fig.4 and Fig.5).

For diagnostic and symptom relief, a pericardial drain was inserted. 1500 mls of bloodstained fluid was drained over day one, with immediate improvement in the patient’s breathlessness. Rather than drying up, there was continued large volume fluid drained from the pericardial space, with 9260 mls removed over an eleven-day period. At the patient’s request, the drain was removed and he was allowed home for Christmas with planned early follow-up.

Five days later the patient was readmitted with breathlessness due to re-accumulation of the pericardial effusion. Surgical pericardial fenestration was performed to create a window to the thoracic cavity, and a second pericardial drain was placed perioperatively. Although the output was initially approximately 500 mls per day, this appeared to be decreasing and the external drain was removed on day four. Unfortunately ten days later, the patient was readmitted with worsening breathlessness, and a five-liter right-sided pleural effusion drained – ongoing output from the pericardium draining into the chest via the pericardial window. Results from the pericardial fluid confirmed a protein-rich exudate, but cytology was negative for malignant cells.

CMR Findings:

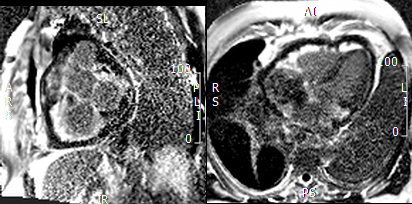

Fig 6. Four chamber view demonstrating pericardial involvement by an extensive tumour, with pericardial thickening and effusion. Mass lesions are seen extending onto the pleura.

Fig 7. Sagittal cardiac MRI image showing mass compressing the superior vena cava. Large pleural/lung masses are seen at the top of image

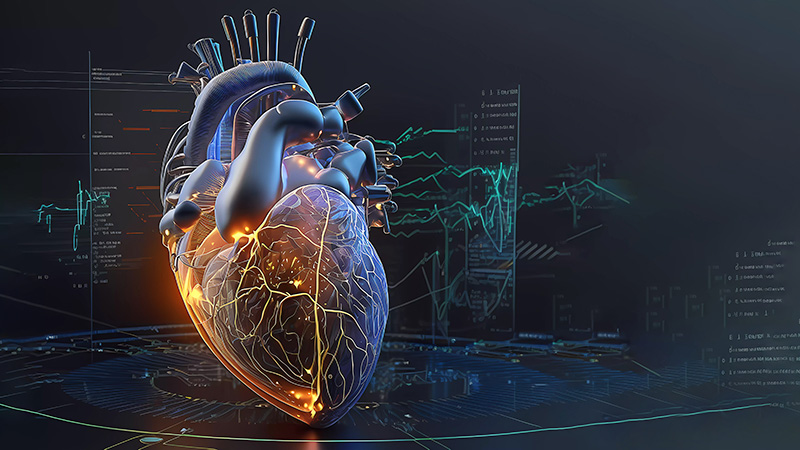

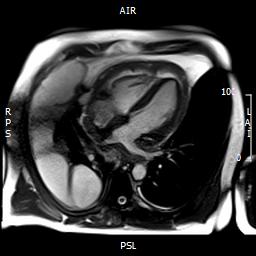

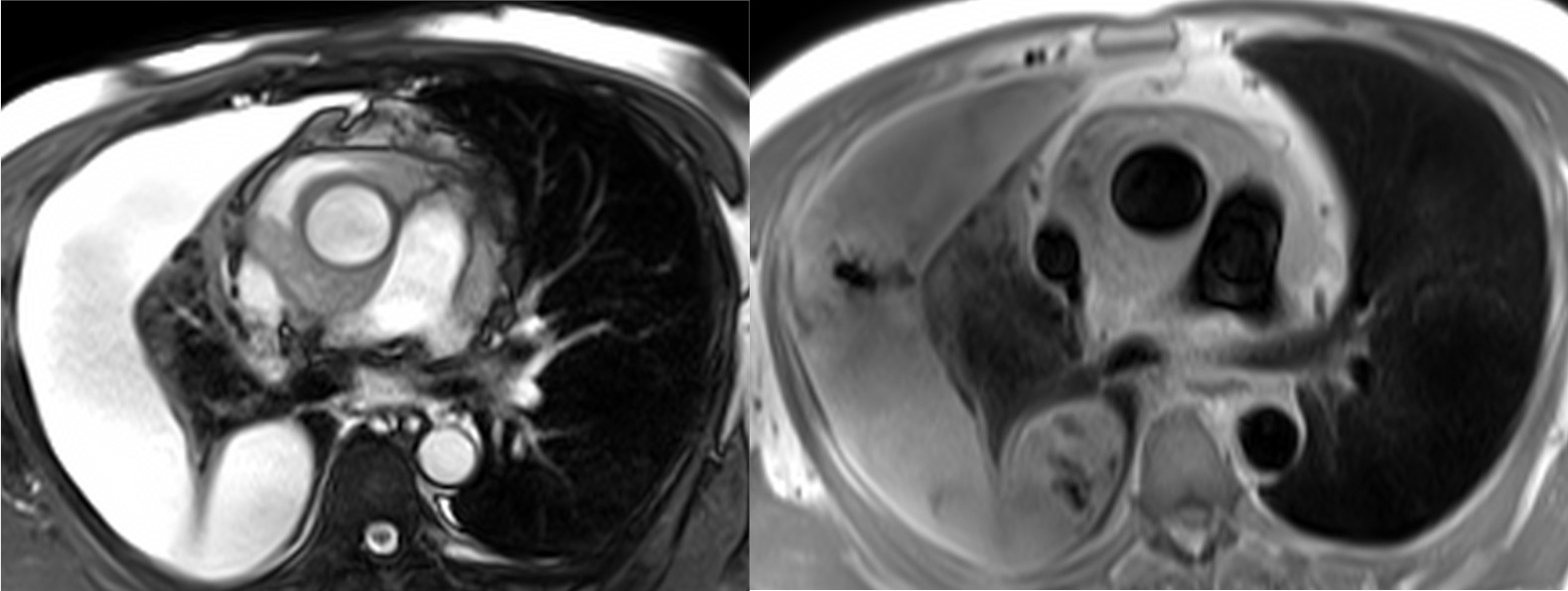

Due to the persistent and dramatic output, a cardiac MRI was performed, which showed a large right atrial tumour with significant extension to the pericardium (Fig 6-7), great vessels and surrounding mediastinal structures, consistent with an aggressive primary cardiac angiosarcoma.

Images show the large irregular mass arising superiorly close to the insertion of the superior vena cava (SVC). The SVC is almost completely obstructed. The sarcoma affects most of the mid and superior mediastinum, encasing the heart and great vessels. There is extensive pericardial spread, which is grossly thickened with mild residual pericardial effusion (recent drainage). (Movie 1-4, and Fig 8).

Fig 8. (SSFP, left) and (HASTE, right) axial images showing the relationship of the mass to mediastinal structures (mass surrounding ascending aorta).

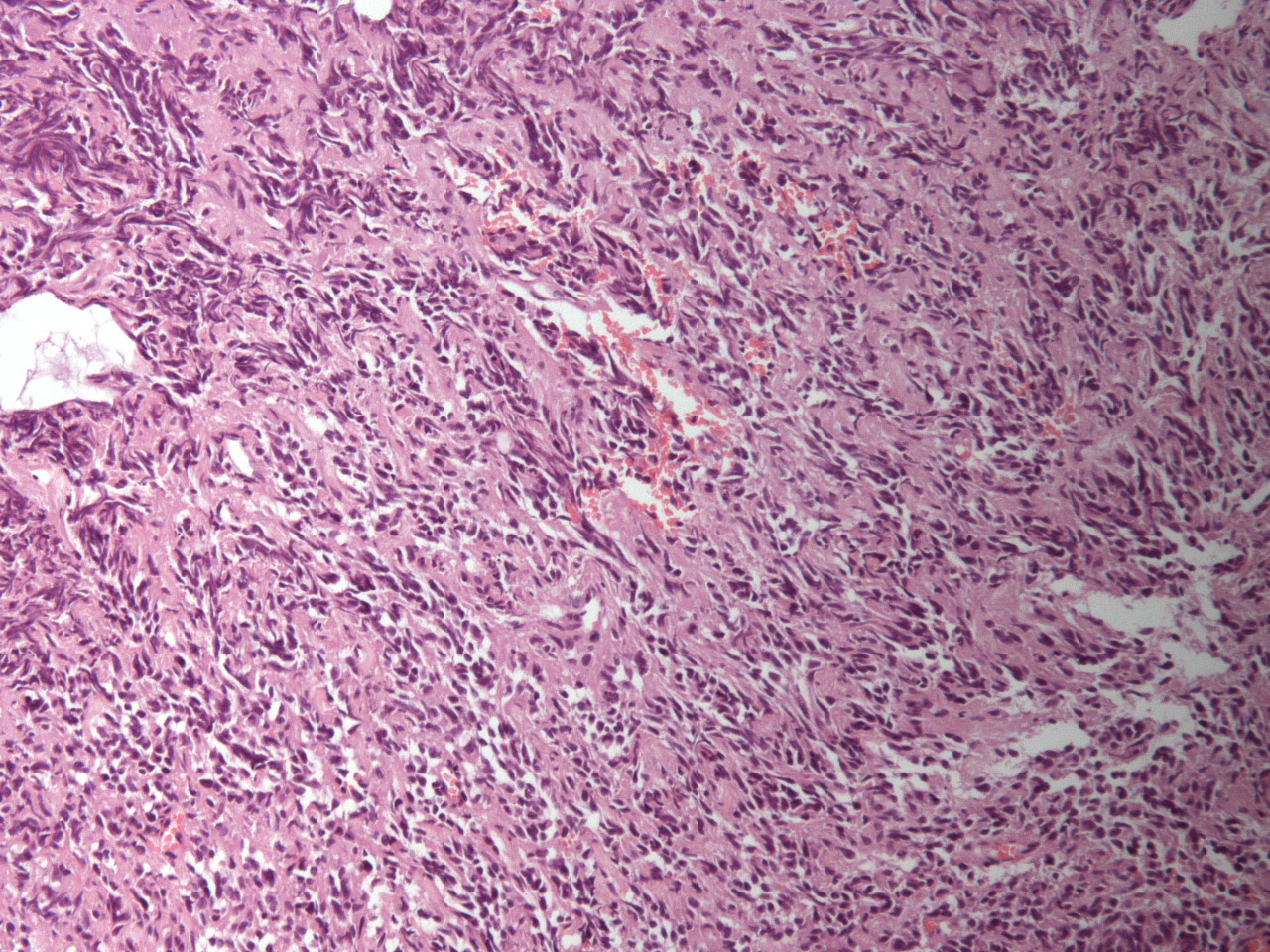

Fig 9. Pericardial histology showing moderately pleomorphic, predominantly epithelioid malignant cells, with foci of spindle cells as well as vascular channels and papillae lined by malignant cells. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed primary cardiac angiosarcoma.

Histological analysis of the pericardium was consistent with a high-grade cardiac angiosarcoma (Fig 9). The mass and the areas of spread show MR signal characteristics in keeping with a malignant tumour: heterogeneous signal on most sequences, high T1 and T2 values as well as patchy uptake of contrast on perfusion and late gadolinium. (Movie 5-6 and Figure 10)

Figure 10. Short axis view of the right venrtricular outflow tract (left) and 4-chamber(right) view demonstrating heterogenous late gadolinium enhancement of the cardiac mass.

The patient was subsequently managed with a long-term indwelling chest drain. Despite five cycles of paclitaxel, with associated clinical improvement, the output from the drain persisted at 300-500mls of fluid daily. Seven months later, he was admitted with worsening breathlessness and died of progressive disease (Fig.11).

Figure 11. Cardiac computed tomography obtained 7 months after cardiac MRI demonstating progression of disease shortly before patient died.

Perspective:

Cardiac tumours are rare1. Twenty five percent of primary cardiac tumours in adults are malignant, the majority of these secondary metastases2. Angiosarcoma is the most commonly encountered primary cardiac malignancy, with a male preponderance and typical presentation between the third and fifth decades of life.

Clinical features associated with cardiac tumours can be divided into three categories: systemic effects (cachexia, malaise, lethargy), embolic phenomena (pulmonary emboli, transient ischaemic attack, stroke, myocardial infarction and visceral ischaemia) and symptoms arising from direct cardiac invasion or mass effect3.

We are reporting the case of a middle-aged patient presenting with a massive and recurrent pericardial effusion due to advanced cardiac angiosarcoma.

Cardiac angiosarcoma is notoriously difficult to diagnose, due to it being relatively rare and presenting with non-specific symptoms and signs. In the case of our patient, cardiac MRI was the imaging modality that revealed the ultimate diagnosis. Multimodality imaging of cardiac tumors has been shown to increase diagnostic accuracy 4, 5.

The prognosis of primary cardiac angiosarcoma remains extremely poor, with a median survival of six months from presentation. It is rarely responsive to chemo-radiotherapy and there is usually extensive cardiac invasion and metastasis at diagnosis, precluding surgical excision.6

Conclusion

Although a rare cause of pericardial effusion, cardiac angiosarcomas are characteristically associated with massive and recurrent effusion. In the West, where tuberculous pericardial effusions are less common, we propose that recurrence of an idiopathic haemorrhagic effusion after drainage should trigger advanced cardiac imaging by cardiac MRI to facilitate early diagnosis of cardiac malignancy.

- Batzios S, Michalopoulos A, Kaklamanis L, Stathopoulos J, Christopoulou M, Koutantos J, et al.: Angiosarcoma of the heart: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(6C):4837-42.

- Peters PJ, Reinhardt S.: The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19(2):230-40.

- Silverman NA.: Primary cardiac tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191(2):127-38.

- Talbot SM, Taub RN, Keohan ML, Edwards N, Galantowicz ME, Schulman LL.: Combined heart and lung transplantation for unresectable primary cardiac sarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(6):1145-8.

- Thakrar A, Farag A, Lytwyn M, Fang T, Arora RC, Jassal DS.: Multimodality cardiac imaging for the noninvasive characterization of intracardiac neoplasms. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132(2):e74-6.

- Vander Salm TJ.: Unusual primary tumors of the heart. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;12(2):89-100.

COTW handling editor: Eddie Hulten, MD