G.K. Gnanappa, M. Krivanek, Phil A. Roberts, J. Ayer

Westmead Children’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia

Clinical History:

An asymptomatic 4-month-old male infant was referred for assessment of a heart murmur. An echocardiogram demonstrated a large (19×11 mm) mass arising from the basal inter-ventricular septum, encroaching on the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), producing mild RVOT obstruction (movie 1).

Movie 1: Echocardiogram – Subcostal long axis color Doppler view shows the mass arising from the basal interventricular septum and protruding into the RVOT with mild flow acceleration.

CMR Findings:

Movie 2: b-SSFP cine image of the RVOT in the sagittal plane shows that the mass arises from the basal interventricular septum and protrudes into the RVOT. The mass is iso-intense to the normal myocardium.

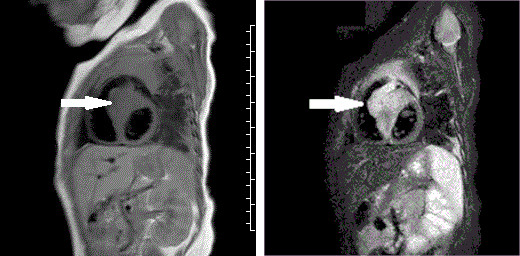

Fig 1a: T1 TSE sequence shows the mass in the basal interventricular septum (arrow), iso-intense with normal myocardium.

Fig 1b: T2 STIR sequence shows the mass in the basal interventricular septum (arrow), hyper-intense compared with normal myocardium.

Fig. 1c: Delayed gadolinium enhancement image shows nulled normal myocardium whereas the mass shows intense enhancement resulting from the accumulation of gadolinium.

Movie 3: First pass contrast enhanced perfusion sequence in the short axis plane of the RV and LV shows earlier and brisk perfusion of the mass, suggestive of a highly vascular lesion. It also shows normal myocardial perfusion.

These features suggested a vascular lesion; an endomyocardial biopsy and coronary angiography were then performed, respectively to aid differentiation between benign and malignant vascular lesions and to better define the relationship to the LAD. Selective left coronary artery angiography demonstrated an instant blush, moderately dilated left coronary artery with unobstructed branches and perforating vessels to the mass (movie 4).

Movie 4: Coronary angiogram

Selective left coronary artery angiogram shows a generous sized left coronary artery with unobstructed branches and perforating vessels to the mass, which blushes with contrast.

The biopsy specimens revealed a large number of tortuous blood vessels of variable wall thickness intertwined within the myocardium. GLUT-1 Immunoperoxidase staining was negative (Figure 2 a, b).

Fig 2a: Multiple irregular vascular profiles within myocardium, some thin-walled with a dilated lumen, others thicker-walled with a narrow lumen. H+E stain. Original magnification x200.

Fig 2b: CD 31 immunostaining of the endothelium highlights the aberrant blood vessels. Original magnification x200.

A diagnosis of vascular malformation (either capillary, venous or combined) was made, as per the criteria of the International Society of the Study of Vascular Anomalies (1).

As the RVOT obstruction was mild and spontaneous involution or non-progression was possible, a conservative approach was followed. Due to the finding of GLUT-1 negative staining, beta blockers were also not trialed as they have proven benefit only in GLUT-1 positive infantile haemangioma (2). The patient has remained well at 3 years follow-up with no significant progression in the size of the mass or RVOT obstruction on echocardiogram.

Conclusions:

A comprehensive CMR has been shown to have high accuracy for the diagnosis of the type of cardiac mass (3). However, differentiation between benign and malignant vascular tumours remains difficult with current CMR sequences, hence the need for endomyocardial biopsy in this case. Our case emphasizes the frequent need for a multi-modal approach to paediatric cardiac tumours.

Perspective:

Cardiac tumours in children are very rare with a reported incidence ranging from 0.027% to 0.08% (3, 4). Although echocardiography is usually the initial screening investigation, CMR has become an important imaging modality in the evaluation of cardiac masses due its ability to accurately define the location and extent of tumours and characterize tissue (5).

Vascular malformations constitute a very small proportion of cardiac masses in both children and adults (6). They may occur anywhere within the heart, but most commonly arise from the ventricles (7). Although most cardiac vascular malformations are incidentally detected, they can present with arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, coronary insufficiency, outflow tract obstruction, embolization, or congestive heart failure. The natural history of cardiac vascular malformation is variable. Spontaneous resolution has been reported in the literature (8). Given this variable natural history, surgical resection has been frequently followed. However, conservative management has also been reported (9) and may be an option depending upon the histological and clinical findings.

We report a rare case of a vascular malformation in an infant, highlighting the important role of CMR in the diagnosis. We also highlight the place of CMR in a multi-modal imaging approach to paediatric cardiac masses.

Click here to access the entire study on CloudCMR

References:

1. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies ©2014 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Available at “issva.org/classification”.

2. Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 12;358(24):2649–51.

3. Isaacs H Jr. Fetal and neonatal cardiac tumors. Pediatr Cardiol 2004;25:252-73.

4. Nadas As, Ellison RC. Cardiac tumors in infancy. Am J Cardiol 1968;21:363-6.

5. Beroukhim RS, Prakash A, Buechel ER, Cava JR, Dorfman AL, Festa P, Hlavacek AM, Johnson TR, Keller MS, Krishnamurthy R, Misra N, Moniotte S, Parks WJ, Powell AJ, Soriano BD, Srichai MB, Yoo SJ, Zhou J, Geva T. Characterization of Cardiac Tumors in Children by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging- A Multicenter Experience. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:1044-54.

6. Uzun O, Wilson DG, Vujanic GM, Parsons JM, De Giovanni JV. Cardiac tumours in children. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 11.

7. Esmaeilzadeh M, Jalalian R, Maleki M, Givtaj N, Mozaffari K, Parsaee M. Cardiac cavernous hemangioma. European Journal of Echocardiography. 2007;8:487-9.

8. Palmer TE, Tresch DD, Bonchek LI. Spontaneous resolution of a large cavernous hemangioma of the heart. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1986;58:184-5.

9. Beebeejaun MY, Deshpande R. Conservative management of cardiac haemangioma. Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2011;12:517-9.

SCMR COTW Associate Editor: Sylvia Chen, MD