Hui Chen1, Xiaohai Ma1*, Lei Zhao1, Zheng Wang1, Feng Gao2, Zhanming Fan1, Jianfeng Shang3, Chiara Bucciarelli-Ducci4

Institutions

1Department of Radiology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

2Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

3Department of Pathology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

4Bristol Heart Institute, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust, UK

*Corresponding Author, Email: maxi8238@yahoo.com

Clinical History

A 71-year-old male with a previous history of working-exposure to glass components was admitted to our hospital with persistent complaints of chest tightness, shortness of breath and edema in the lower limbs that started 3 months prior to his admission. An echocardiogram from a local hospital identified a nodule on the right-sided of the pericardium and large pericardial and pleural effusions. Percutaneous drainage was performed and 30 mL were obtained from the pericardium and 500 mL from the pleurae, both of hemorrhagic appearance. Biochemical analysis of pericardial and pleural fluids was not performed and cytological analysis was negative for malignant cells. Medical treatment was initiated and the patient remained asymptomatic for the following 3 days. The patient’s symptoms recurred and rapidly worsened so he was admitted to our institution for further examination and treatment.

At admission, his vital signs were stable with a blood pressure of 112/74 mmHg and no pulsus paradoxus. Ewart and Kussmaul’s sign were present and heart sounds were diminished. The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable.

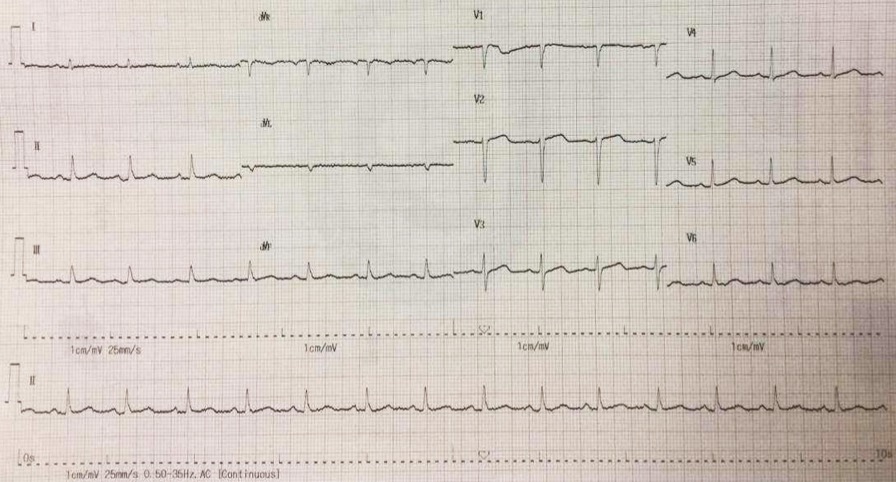

His initial ECG showed sinus rhythm with a rate of 90 bpm and slow progression of R wave in leads V1 to V3. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram shows sinus rhythm of 90 bpm and slow progression of R wave in leads V1 to V3.

Routine blood laboratory tests were unremarkable, but levels of D-dimer and cancer embryo antigen (CEA) were markedly elevated: 453 ng/mL (normal range 0-243) ng/mL and 5.1 ng/mL (normal range 0-5) ng/mL, respectively.

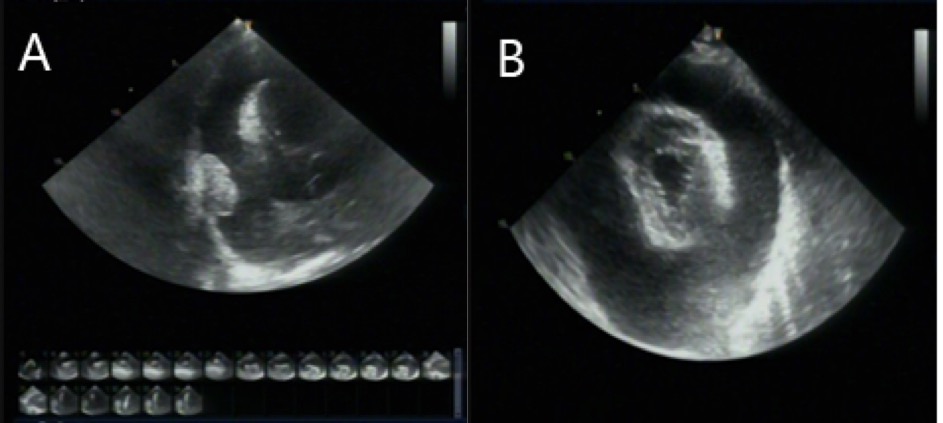

A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a nodular lesion on the right side of the pericardium with normal left ventricular ejection fraction and cardiac valves (Figure 2).

Figure 2A – 2B. The transthoracic echocardiography showed a thickened pericardium with massive pericardial effusion.

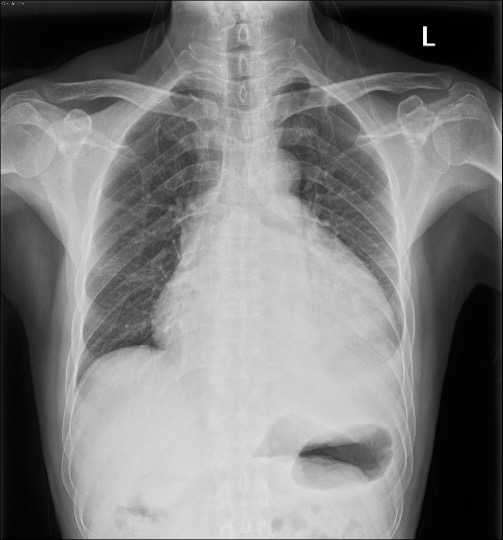

A chest X-ray film showed an obviously increased cardiac contour (Figure 3).

Figure 3. PA view of the chest X-ray film. The cardiac size is enlarged with “water bottle” appearance suggesting pericardial effusion and a small amount of pleural effusion.

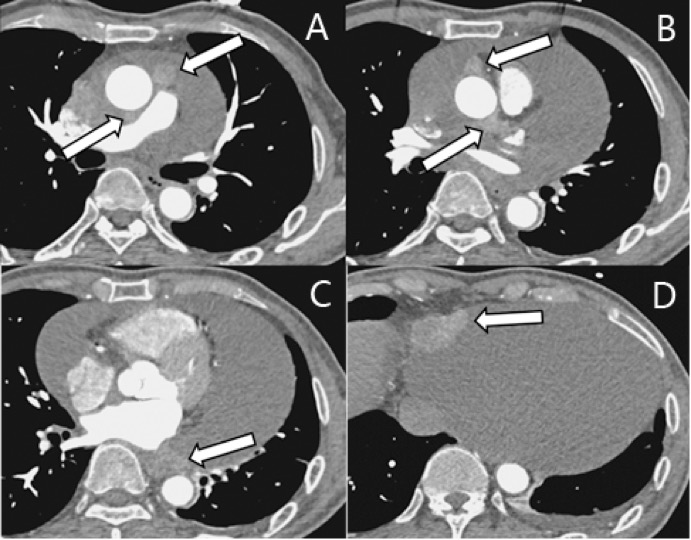

Chest computed tomography imaging revealed a large pericardial effusion and a small pleural effusion without lung parenchymal mass lesions or pleural nodules (Figure 4).

The patient then underwent ECG-gating aortic computer tomography angiography (CTA), which showed multiple irregular nodules in the right pericardium and transverse pericardial sinus in addition to a large pericardial effusion. Nodules were close to the pericardium and were isodense in the arterial phase. There was no significant obstructive coronary artery disease (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The aorta CT angiography examination showed multiple tumors (arrows) and massive pericardial effusion

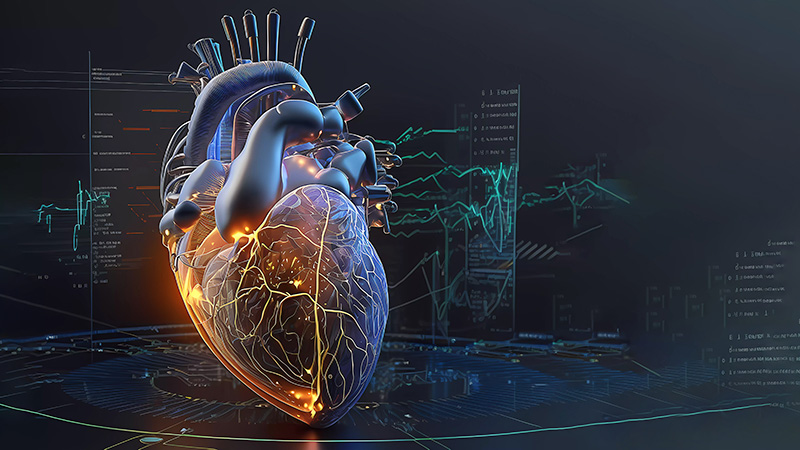

CMR findings

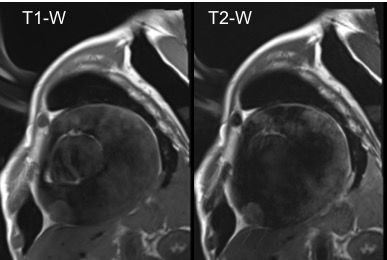

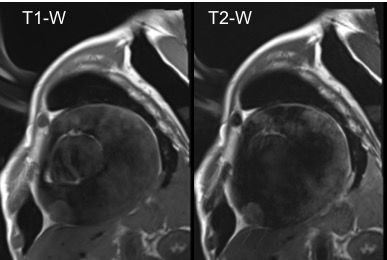

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed. Several nodules were seen on the right side of the pericardium, at the level of the left atrial appendage, left pulmonary vein, and superior pericardial recess. These nodules were low signal intensity in the cine (Videos 1-3) and T1 weighted images, and equal or high signal in T2 weighted images (Figure 6). The heart swing in the inhomogeneous high signal pericardial effusion can be seen in the cine images.

Videos 1. SSFP 4-chamber view demonstrated “swinging heart” in massive pericardial effusion.

RA and RV diastolic collapse is seen suggesting early signs of hemodinamically significance.

Videos 2. SSFP 2-chamber view demonstrated “swinging heart” in massive pericardial effusion.

Videos 3. SSFP short-axis view demonstrated “swinging heart” in massive pericardial effusion.

Figure 6. Short-axis view TSE Left side. T1-W image. Right side. T2- W image. Showing similar signal intensity of the mass in T1-W and higher in T2-W.

Although the nodules had homogeneous enhancement in late gadolinium enhancement imaging (LGE), no LGE was identified in the myocardium (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) demonstrating homogeneous delayed enhancement of pericardial tumors (arrows). A. LGE 4-chamber view. B. LGE 2-chamber view. C. LGE short-axis view.

Cardiac surgery was performed via mid-sternum thoracotomy because of cardiac tamponade. Hemorrhagic pericardial fluid (1500 ml) was drained and three masses of hard, cauliflower-like, white to tan appearance were seen. These were located in the inferior margin of the right ventricular pericardium, the junction of the superior vena cava into the right atrium and the anterior wall of the pericardium near the invagination and were 5cm x 5cm, 5cm x 5cm and 1.2cm x 1.5cm, respectively. Interestingly, those masses didn’t have a clear tissue interphase with the pericardium.

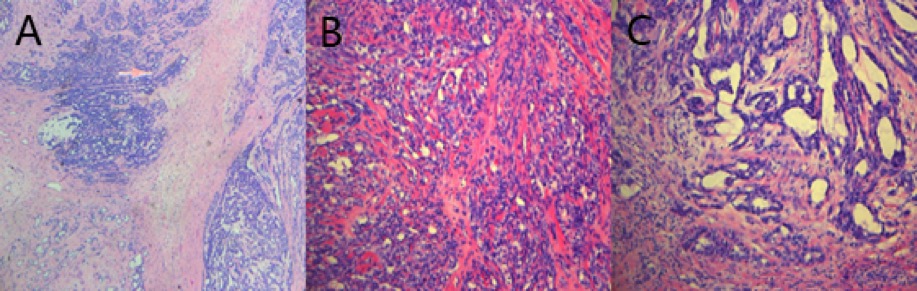

Microscopic examination from resected pericardial tissues revealed a biphasic differentiated malignant mesothelioma. Local tumor cells showed invasive growth, and were arranged in glandular tubular, adenoid cystic and microcapsule patterns with mild to moderate grade nuclear atypia and mitotic figures which are typically seen in epithelial-type malignant mesothelioma (Figure 8). Hemorrhage and necrosis were also noted in the tumor. Immunohistochemistry was positive for AE/AE3, Vimentin, EMA, CK7, WT1, Calretinin, D2-40, MC and BcL-2, which supported the diagnosis of a biphasic primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma.

Figure 8. Microscopic examination showed invasive growth, arranged in a glandular tubular, adenoid cystic and microcapsule pattern with mild to moderate grade nuclear atypia and mitotic figures. Tumor hemorrhage and necrosis were noted.

After surgery, the patient did well. His symptoms were completely relieved; however, a few months later his symptoms recurred and medical options are still being considered for him.

Conclusion

PMPM is a rare and aggressive tumor with a median survival time of about 6–10 months. CMR can provide not only accurate information about tumor location and extent of myocardial infiltration, but give hints on the nature of the nodules in different sequences.

Perspective

The incidence of PMPM is about 0.0022% [3] with a male to female ratio of 3:1.(4) Unlike pleural mesothelioma, the relationship of PMPM and asbestos is unclear.(5,6) The pleural effusion of mesothelioma is often hemorrhagic, and is usually rich in protein, hyaluronic acid and LDH, with low levels of glucose and pH value. A high level of hyaluronic acid suggests a malignant mesothelioma. Unfortunately, in our case the level of hyaluronic acid was not measured in the initial percutaneous or in the surgically obtained pericardial and/or pleural fluids.

Ohnishi et al described that in the evaluation of PMPM, CMR not only can be used for qualitative and quantitative diagnosis of pericardial effusion, but also for the infiltration depth and extent of involvement in the pericardium.(7) In our case, tissue characterization in T1-W, T2-W and LGE sequences helped identify the highly suggestive hemorrhagic component of the pericardial fluid, the absence of inflammation of the pericardium, and the nodular masses which were isointense in T1-W and hyperintense in T2-W images. This specific tissue characterization appearance of fluid, pericardial layers and masses of our patient was consistent with the previously described CMR characteristics of pericardial and pleural mesothelioma.

In PMPM, calretinin is expressed in normal, hyperplastic and mesothelioma cells, but epithelial cells generally do not express calretinin. This finding has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. CK, Vimentin and expression of EMA in malignant pericardial mesothelioma are also higher in malignant mesothelioma. Additionally, the positive rate of Wilm’s Tumor-1 (WT-1) in malignant mesothelioma is also very high.

PMPM is a diagnosis of exclusion, because the lack of clear histological features for classifying it as pericardial mesothelioma. Chun et al. put forward the diagnostic bases for this tumor: the tumors are limited to the pericardium; only metastases to lymph nodes; and there are no other primary tumors. In the case of death, the diagnosis should be done by autopsy.(8)

References

- Mukai K, Shinkai T, Tominaga K, Shimosato Y. The incidence of secondary tumors of the heart and pericardium: a 10-year study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1988;18(3):195–201

- Gössinger HD, Siostrzonek P, Zangeneh M, Neuhold A, Herold C, Schmoliner R, Laczkovics A, Tscholakoff D, Mösslacher H. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in a patient with pericardial mesothelioma.Am Heart J. 1988;115:1321–2

- Butz T, Faber L, Langer C, Körfer J, Lindner O, Tannapfel A, et al. Primary malignant pericardial mesothelioma-a rare cause of pericardial effusion and consecutive constrictive pericarditis: A case report.J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9256.

- Van De Water JM, Allen WA. Pericardial mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1967;3:162–165.

- Mensi C, Giacomini S, Sieno C, Consonni D, Riboldi L. International Journal of Hygiene and Pericardial mesothelioma and asbestos exposure. Int J Hyg Environ Health [Internet]. 2011;214(3):276–9.

- Mezei G, Chang ET, Mowat FS, Mbbs SHM. Annals of Epidemiology Epidemiology of mesothelioma of the pericardium and tunica vaginalis testis. Ann Epidemiol [Internet]. 2017;27(5):348–359.e11.

- Ohnishi J, Shiotani H, Ueno H, Fujita N, Matsunaga K. Primary pericardial mesothelioma demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging. Jpn Circ J. 1996 Nov;60(11):898-900.

- Chun PK, Leeburg WT, Coggin JT, Zajtchuk R. Primary pericardial malignant epithelioid mesothelioma causing acute myocardial infarction. Chest. 1980 Apr;77(4):559-561.

Case prepared by Lilia M. Sierra-Galan, MD MCvT, FACC, FSCCT, Associate Editor, SCMR Case of the Week. American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico.