Steve Muyskens MD and Shelly Porterfield BSRS RT(R)(MR)

Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth, TX

Clinical History:

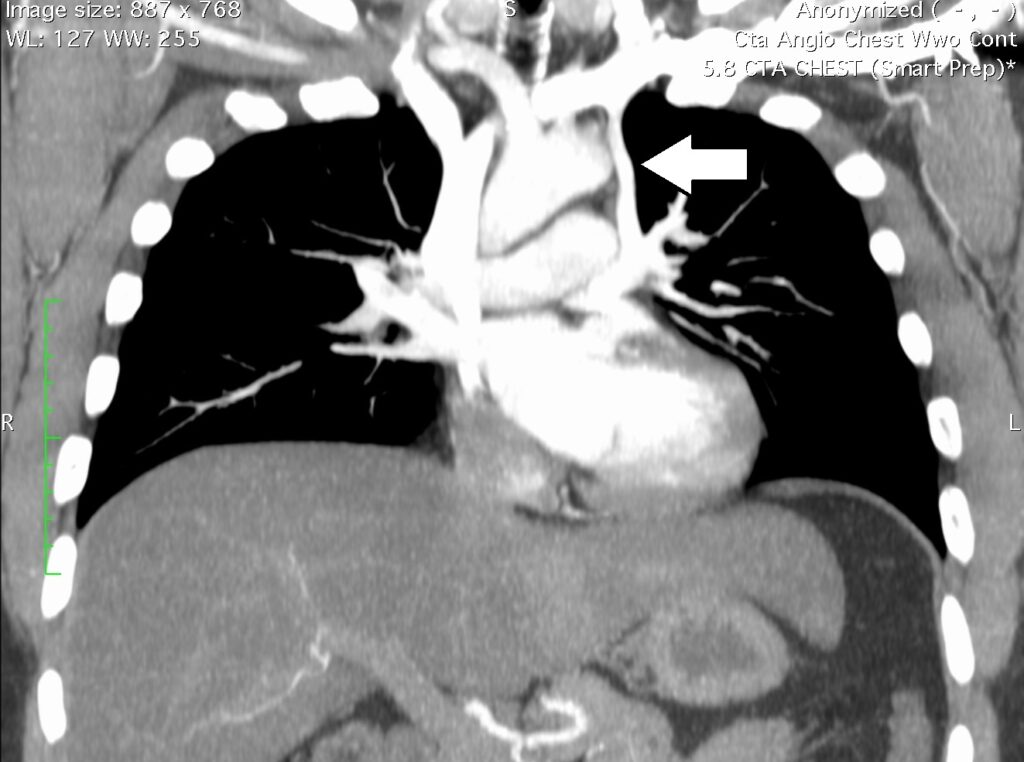

A 39-year-old male with a history of obesity and poorly controlled essential hypertension presented to the emergency department with chest pain and shortness of breath. A CT angiogram demonstrated normal coronary anatomy. However, a vascular structure was noted coursing from the innominate vein toward the left atrium (Image 1). This was interpreted as a persistent left superior vena cava (LSVC) with intact bridging vein. The patient was referred to a cardiologist for further evaluation of his symptoms and management of his hypertension. 2-dimensional (2D) transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) demonstrated a structurally normal heart, mild qualitative dilation of the left atrium (LA), and no apparent atrial or ventricular septal defects. There was no significant atrioventricular valve insufficiency. The right ventricle (RV) and left ventricle (LV) were normal in regards to size, global systolic function, and regional wall motion. A bubble contrast study was performed to exclude intracardiac shunting.

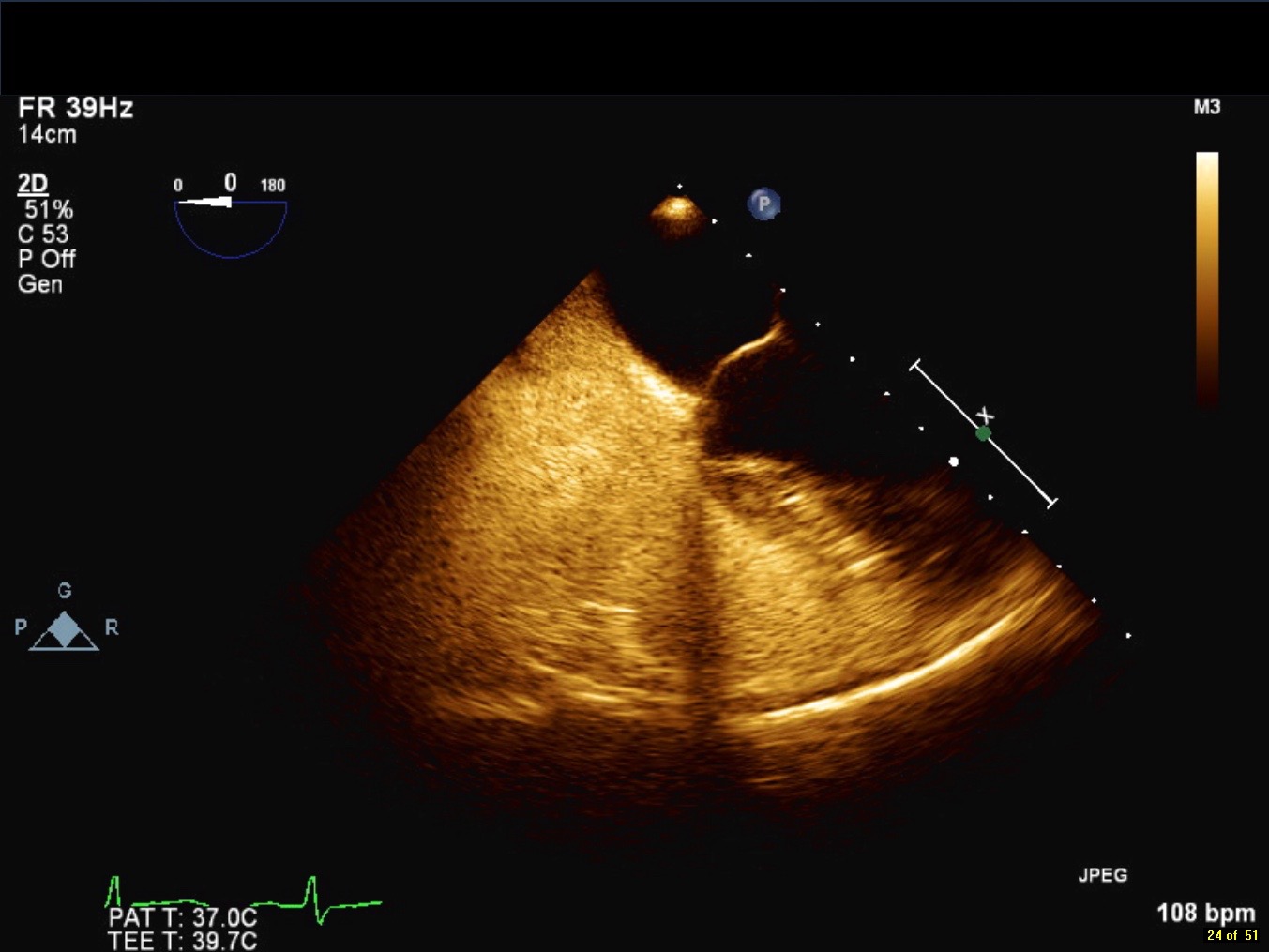

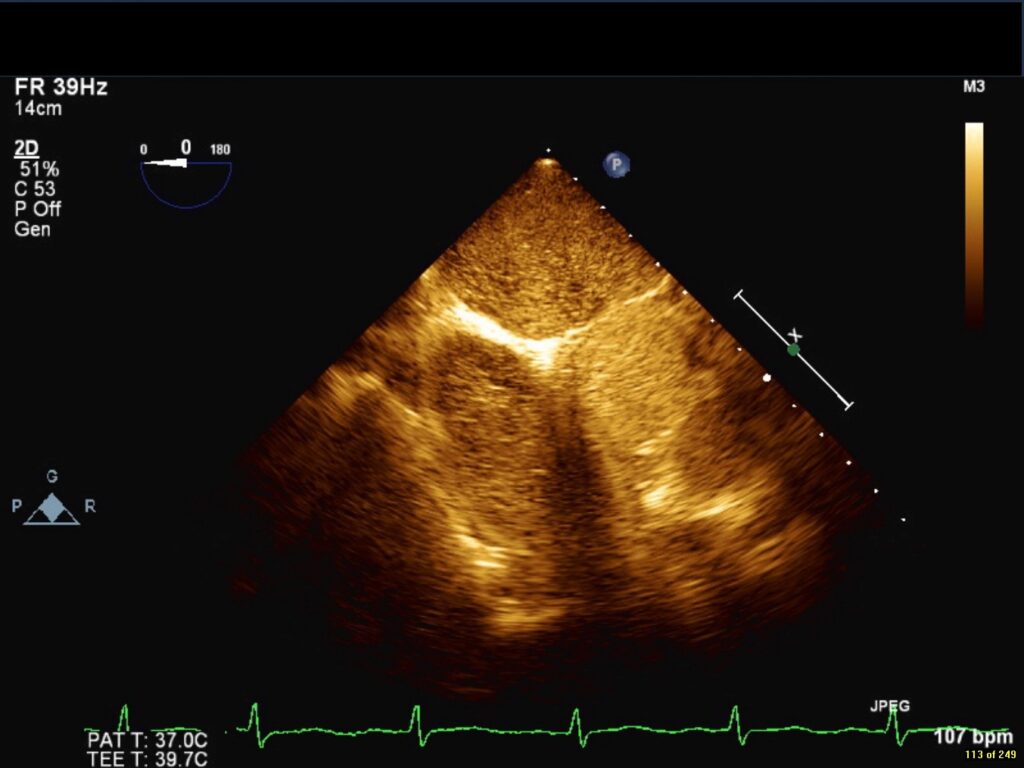

Right arm peripheral bubble contrast injection with Valsalva maneuver (Image 2, Movie 1) opacified the right atrium (RA) and RV. No contrast was observed in the LA or LV. Left arm peripheral bubble contrast injection with Valsalva maneuver (Image 3, Movie 2) filled the RA and LA simultaneously. The patient had normal oxygen saturations on room air. He was referred to our institution for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) to further define intracardiac anatomy and shunting.

Image 1. CTA oblique coronal multiplanar reconstruction demonstrating vessel (white arrow) from the innominate vein to the left atrium.

Movie 1 and Image 2. 2-D TEE demonstrates right atrial and right ventricular opacification with right arm peripheral bubble contrast injection.

Movie 2 and Image 3. 2-D TEE demonstrates simultaneous left and right-sided opacification with left arm peripheral bubble contrast injection.

CMR Findings:

All CMR images were obtained on a 3.0 Tesla Verio (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Steady-state free precession cine images (Movies 3 and 4) demonstrated normal biventricular size (RV end-diastolic indexed 70.9 ml/m2, LV end-diastolic volume indexed 63.8 ml/m2) and systolic function (RVEF 55%, LVEF 55%).

Movies 3 and 4. Steady-state free resonance CMR cine imaging in a short axis and four chamber slice demonstrates normal biventricular size and function.

The atrial and ventricular septa appeared intact. Calculated RV and LV stroke volumes suggested a Qp:Qs of approximately 1 (RV stroke volume indexed 39 ml/m2, LV stroke volume indexed 39.1 ml/m2). Phase contrast flow analysis of the pulmonary artery and aorta confirmed a Qp:Qs of 1.04.

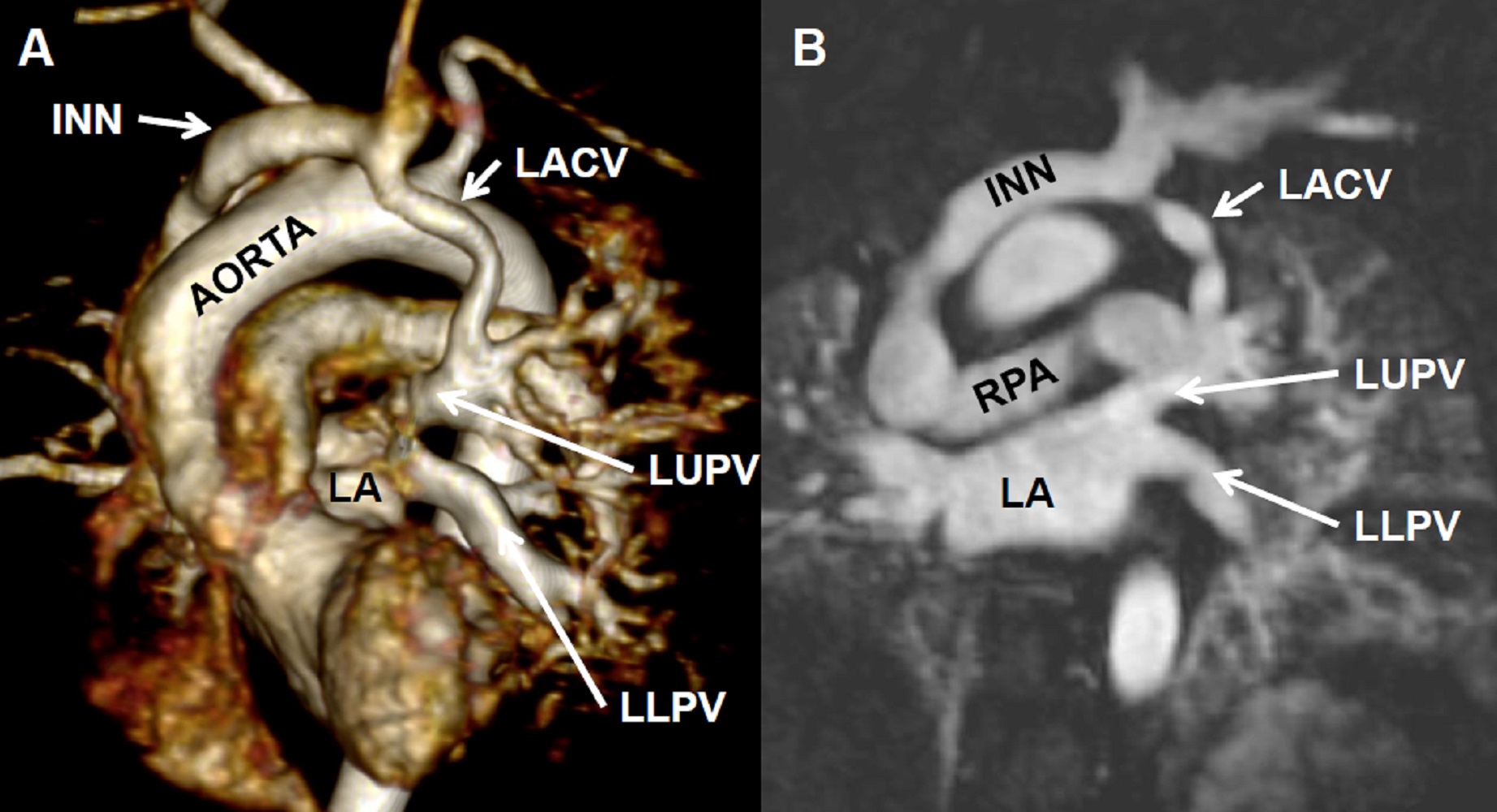

Dynamic breath-hold contrast enhancement magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) (Movie 5) with rapid infusion (4 ml/sec) of 0.3 ml/kg of gadopentetate in the left hand was performed to evaluate arterial and venous anatomy. A 1.0 cm x 1.2 cm diameter vessel was seen coursing between the proximal left upper pulmonary vein and the innominate vein (Image 4) during the pulmonary venous return phase. The left upper pulmonary vein returns normally to the left atrium (Image 5). Free-breathing phase contrast flow analysis demonstrated low velocity superiorly directed flow (Image 6 and 7). Breath-held phase contrast imaging with Valsalva was not performed due to prior bubble contrast TEE demonstrating right-to-left flow. There was no hyperenhancement of late gadolinium enhanced images. There was no evidence of a LSVC. The patient was diagnosed with a levoatriocardinal vein (LACV).

Movie 5 and Image 4: Dynamic contrast enhanced MRA demonstrates left-to-right shunting through the levoatriocardinal vein (LACV) (white arrow) draining from the left upper pulmonary vein to the innominate vein.

Image 5: Contrast enhanced MRA with 3D reconstruction (A) and off axis reconstruction (B) demonstrates the left upper pulmonary vein (LUPV) returns normally to the left atrium (LA). Innominate vein = INN; Levoatriocardinal vein (LACV); Left lower pulmonary vein = LLPV; Right pulmonary artery (RPA)

Images 6 and 7. Phase contrast flow analysis demonstrating superiorly directed flow in the LACV (red circle).

Conclusion:

The patient was educated regarding the diagnosis of LACV, hemodynamic significance, and potential consequences. He had no history of embolic phenomenon, pulmonary hypertension, or right-sided heart failure. He elected to be followed clinically with no intervention planned. Dynamic magnetic resonance angiography, phase contrast imaging, and ventricular volumetric analysis make CMR ideal for the assessment of anomalous venous anatomy.

Perspective:

A LACV is an extremely rare vascular anomaly characterized by the connection of the left atrium, or proximal pulmonary veins, to any venous structure originating from the cardinal system. Early in cardiac and pulmonary formation, the primitive lung buds and common cardinal veins drain to the splanchnic plexus. Around four weeks of gestation, the common pulmonary vein develops and connects to the left atrium. Subsequently, connections to the splanchnic plexus obliterate and the common pulmonary vein is incorporated into the left atrium. Between the 5th and 7th weeks, the thymicothyroid anastomosis forms, directing left-sided systemic venous flow to the right common cardinal vein. The right common cardinal vein evolves into the right superior vena cava, and the left common cardinal vein involutes leaving the coronary sinus. Therefore, the LACV is embryologically distinct from a LSVC and may be inappropriately identified, as in this case, due to a lack of recognition.

In patients with normal cardiac anatomy, a persistent LSVC drains anterior to the left pulmonary veins, or hilum, and joins the coronary sinus along the left atrioventricular groove. The innominate vein is often absent, or hypoplastic secondary to diminished flow. Conversely, a LACV typically arises from the posterior aspect of the left atrium, or proximal pulmonary veins. The LACV has been described draining to the superior vena cava, jugular veins, and innominate veins (1). While a persistent LSVC is considered a normal variant in 0.5% of the general population, a LACV creates a pathological connection to the left atrium.

In obstructive left-sided lesions with an intact or restrictive atrial septum, elevated left atrial pressures may result in persistence of the LACV (1). Often, the LACV is the only method of egress from the left atrium. This anomaly is rare and was first described by McIntosh in 1926 (2). Even rarer is the presence of a LACV with normal intracardiac anatomy and pulmonary venous return. To our knowledge, only four cases have been published describing this anomaly (1, 3-5). Prior cases described primarily younger patients (24 years, 18 years, and 5 years) with hemodynamically significant left-to-right shunting and right-sided dilation of the heart. These patients underwent successful surgical ligation or percutaneous device occlusion. Only one case of bidirectional shunting through a LACV in the presence of normal intracardiac anatomy has been described. This patient subsequently underwent percutaneous device embolization for a history of transient ischemic attacks.

A persistent LACV associated with normal intracardiac anatomy is an extremely rare anomaly. Appropriate understanding of both a LSVC and LACV are essential for it’s correct diagnosis. Clinically, the degree of shunting appears to be multifactorial, and is important for the surveillance of right-sided heart failure, embolic sequelae, and procedural planning.

Click here to view case on CloudCMR. Click ‘Show me the scan’

References:

1. Bernstein HS, Moore P, Stanger P, Silverman NH. The levoatriocardinal vein: morphology and echocardiographic identification of the pulmonary-systemic connection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995; 26:995-1001.

2. McIntosh CA. Cor biatriatum triloculare. Am Heart J. 1926; 1:735-744.

3. Jaecklin T, Beghetti M, Didier D. Levoatriocardinal vein without cardiac malformation and normal pulmonary venous return. Heart. 2003; 89:1444.

4. Odemis E, Akdeniz C, Saygili OB, Karaci AR. Levoatriocardinal vein with normal intracardiac anatomy and pulmonary venous return. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011; 4(2):183-185.

5. Cullen EL, Breen JF, Rihal CS, Simari RD, Ammash NM. Levoatriocardinal vein with partial anomalous venous return and bidirectional shunt. Circulation. 2012; 126(12):e174-7.

Case prepared by:

Jason Johnson, MD MHS

Associate Editor, SCMR Case of the Week

Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital

University of Tennessee Health Science Center