M. Farhan Nasser, MD1; Yassar Nabeel, MD2; Rajiv Shah, MD3, J. Michael Kennen, DO3; Ashish Aneja,MD 2

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Akron General, Akron, OH, USA

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Metrohealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

3Department of Radiology, Metrohealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University. Cleveland, OH, USA

Case Published in the Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: Click here for the link

Click here for PubMed Reference to Cite this Case

Clinical History

A 46 year old woman presented with complaints of generalized abdominal pain. Initial work up with a Computerized Tomography (CT) scan of abdomen/pelvis revealed wedge shaped areas of low attenuation in her spleen and right kidney which was consistent with infarction. She also had adynamic ileus secondary to bowel infarction along with findings suggestive of an embolus in her superior mesenteric artery (SMA). CT also revealed a possible 2 x 4.1 cm “mass” within the left ventricle of the heart. Empiric anticoagulation with heparin was started and she underwent urgent exploratory laparotomy, small bowel resection, SMA embolic material removal and patch angioplasty of the SMA.

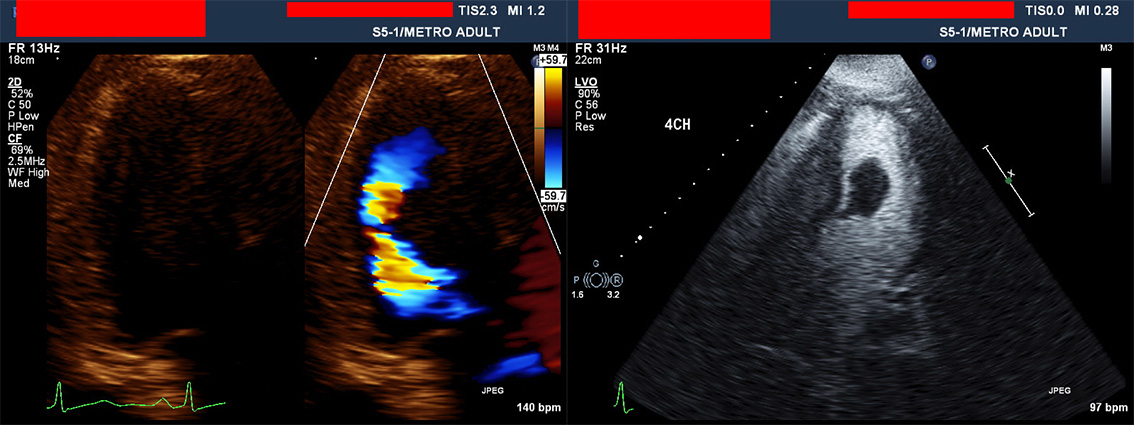

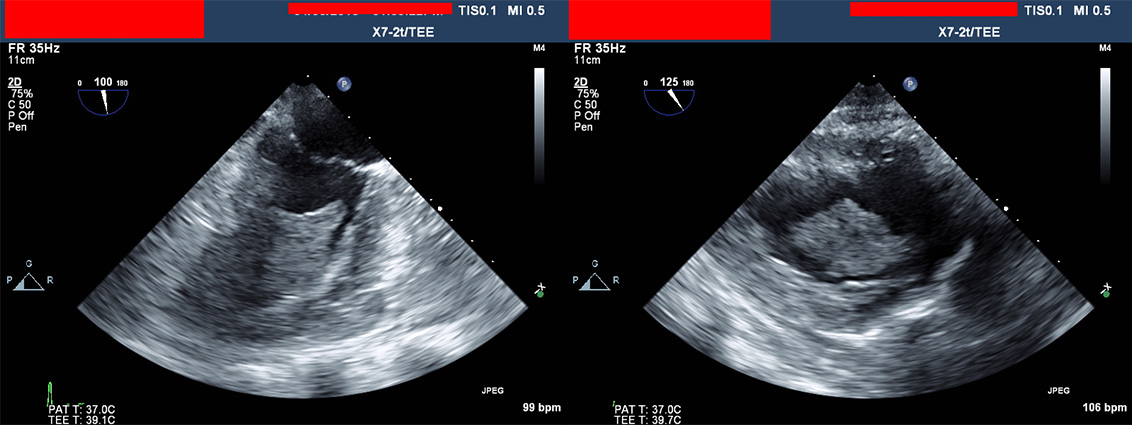

Transthoracic echocardiogram on the day after admission showed an ejection fraction of 65% without LV wall motion abnormalities. It also confirmed a “mass” in the left ventricle near the outflow tract which measured 3.2 x 2.3 cm (see transthoracic echo images). The mass was hypovascular and pedunculated with an attachment to the basal anteroseptal wall. Second look surgery on the following day showed that the areas of questionable viability from her first surgery were frankly ischemic, as a result of which she underwent ileostomy, jejunostomy, leaving only 20cm of her viable terminal ileum and entire colon. She underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram 2 days later, which corroborated the transthoracic echo findings, revealing a “mass” in the left ventricle (selected transesophageal echo images appear below).

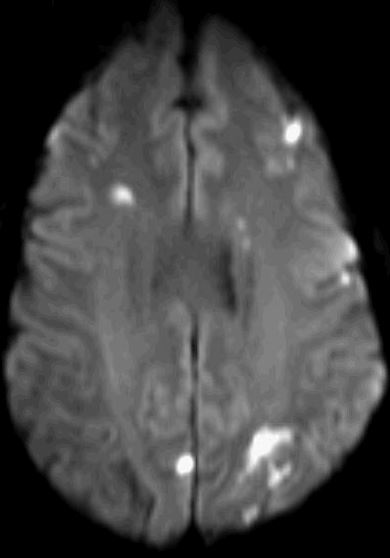

Initial interpretation of the “mass” favored a myxoma but a thrombus was also suspected. A cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) scan performed a week after her admission showed findings consistent with a thrombus that had embolized from the left ventricle into the aortic arch. On the following day a brain MRI revealed multiple cerebral infarctions in her ICA territory. Pathology results confirmed that the SMA embolic material was indeed thrombus. Due to difficulty managing her heparin, her anticoagulation was changed to enoxaparin. The patient was found to suffer from left middle cerebral and posterior cerebral artery strokes when she had symptoms of right hemiparesis, dysarthria and word finding difficulty. Thrombolysis or thrombectomy were not undertaken as the patient was anticoagulated and had poor carotid access. She had residual right side hemianopsia with no other residual deficits.

Her anticoagulation was then changed to fondaparinux, to be continued indefinitely. She was ultimately discharged to inpatient rehabilitation with plans to be evaluated later for intestinal transplant due to short gut syndrome. After rehabilitation, she was able to walk but used wheelchair and walker for ambulating a longer distance.

Echo and Brain MRI Images

Above: Transthoracic Apical LV views with and without Ultrasound Enhancing Agent

Above: Transesophageal Echocardiographic Views of the LV in Mid-Esophageal Two-Chamber and Transgastric Projections

Above: Diffusion Weighted Brain MRI showing Multifocal Infarctions Consistent with Embolism

Cardiac MRI findings

The CMR revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% with normal dimensions and function without any mass in the left ventricle.

Figures 1-4. Four chamber cine and three selected short axis cines showing normal LV function and absence of mass in the LV cavity

The patient had a bovine aortic arch anatomy and was found to have a 2.8 x 1.9 cm occlusive thrombus in the proximal aortic arch extending into the proximal innominate artery.

Figures 5 and 6. SSFP cines of the aortic arch in short-axis and sagittal planes showing a low signal intensity mass in the aortic arch, entering and occluding the brachiocephalic trunk

Figures 7 and 8. The thrombus had a short T1 consistent with methemoglobin as shown in the black-blood images above.

Figures 9 and 10. Images were consistent with a bland thrombus that had completely embolized from the left ventricle on the MR angiogram and thrombus sequences (TI time ~ 600 ms).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report a case of an LV thrombus that embolized in its entirety to the aortic arch, innominate artery and caused multi focal infarcts in her SMA and internal carotid artery distributions. Our report emphasizes the use of comprehensive MR imaging in the assessment and differentiation of cardiac masses. In our patient, even though the “mass” had embolized by the time MR was performed, its tissue characterization abilities were critical in identifying that it was indeed a thrombus. The mass had a high signal and a short T1 consistent with methemoglobin. Overall, due to a larger field of view, greater spatial resolution, lack of attenuation, and ability to image in any plane along with its superior tissue characterization properties, MR is the gold standard for assessment of cardiac masses (6).

Perspective

There have been several case reports of thrombus mimicking cardiac tumors. Left ventricular thrombus formation is a well-known complication of a myocardial infarction, LV aneurysm, cardiomyopathy or a hypercoagulable state. It is uncommon for a thrombus to form in a normal LV in the absence of a wall motion abnormality. Initial interpretation of the “mass” favored myxoma due to the absence of these factors. The specific etiology for formation of thrombus is unclear as her imaging and hypercoagulable work up did not point to a specific cause. Notably, she was on medroxyprogesterone injections but her hypercoagulable work up was negative for anticardiolipin antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, lipoprotein A, beta 2 glycoprotein, and JAK (Janus Kinsae) 2 mutation.

Imaging plays a critical role in establishing a diagnosis and planning management. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE), and CMR have all been used to detect the presence of cardiac tumors and thrombi (1). CMR has a superior sensitivity and specificity of 88 +/-9% and 99+/-2% in comparison to echocardiography and has enhanced ability to identify thrombi and differentiate from other cardiac masses because of superior tissue characterization (2).T1 weighted MR imaging has been successful in identifying acute/subacute thrombi due to the short T1 effect of methemoglobin (3-4). On CMR, recent thrombi have a shorter T1 than old thrombi due to the presence of methemoglobin and hence a brighter signal on T1 weighted images (5).

It is important to establish whether the mass is a tumor, thrombus or vegetation due to their different complications and therapeutic implications. Treatment of thrombi includes adequate anticoagulation. In our patient, no intervention was performed as the thrombus had already embolized into the aortic arch.

1) Sheheryar, Q. (2013). A Case of Primary Cardiac Sarcoma. Journal Of Clinical Trials In Cardiology, 1(1). doi: 10.15226/2374-6882/1/1/00106