Dr. Mekkaoui Abderrahmane, Dr. Chergui Abdellah

Établissement Hospitalier Universitaire 1er Novembre d’Oran, Oran, Algeria

Clinical History:

A 17-year-old female presented to the hospital with complaints of shortness of breath and coughing. She had no specific medical history, and lived in a rural area in Algeria, with a daily intake of unpasteurized milk. Initially, a chest X-ray (CXR) (Figure 1) was performed, revealing an enlarged mediastinum with an abnormal heterogeneous heart shadow.

|

Figure 1: Chest X-ray showing an enlarged and heterogeneous cardiac silhouette, with a cardio-thoracic ratio of 70%.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm with peripheral low QRS voltage and inverted T waves in all leads. A transthoracic echocardiogram (Movies 1-2) indicated normal biventricular systolic function with multiple masses observed in both atria and the inferior and lateral left ventricular (LV) walls and apex.

|  |

Movies 1 & 2: Transthoracic echocardiogram in parasternal long & short axes views showing multiple masses involving the inferior and lateral walls of the left ventricle and inside the left atrium.

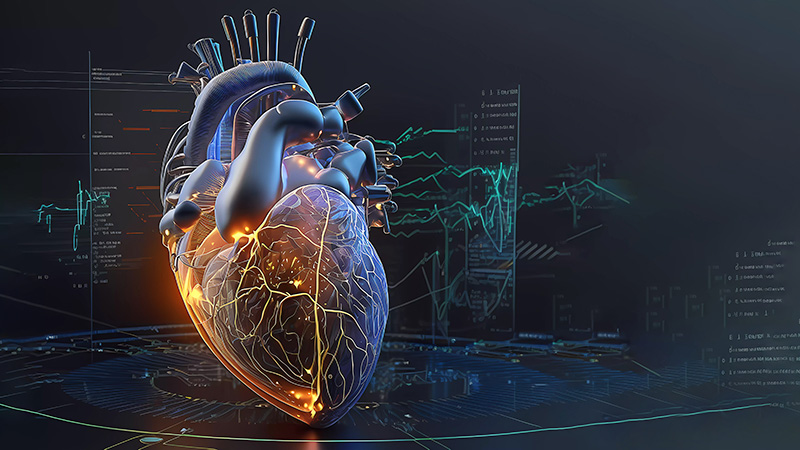

Considering the patient’s lifestyle and the typical pattern of the cysts, a hydatid cardiac cyst was strongly suspected. Consequently, a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) study and a cardiac computed tomographic angiogram (CTA) were performed to evaluate the anatomical involvement of the cysts, other extracardiac locations, and to plan surgery if necessary.

CMR Findings:

A CMR scan was conducted using a 1.5 Tesla Siemens Aera MRI scanner. The cine sequences demonstrated normal systolic function of the LV with an ejection fraction (EF) of 58% and normal chamber volumes. However, there were two large cysts with regular contours along the lateral and inferior walls of the LV pushing and invading the myocardial walls (Movie 3). In addition, multiple multilobed cysts on the roof of the left atrium with compression of left upper pulmonary vein were noted. There was also an intraluminal cyst developing inside the left auricle (Movie 4).

|

Movie 3: Cine balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequence of a 3-chamber view showing two large cysts with regular contours inferior to the inferolateral wall of the LV and a large multilobed cyst superior to the anteroseptal wall.

|

Movie 4: Cine bSSFP sequence of a four-chamber view showing multiple multilobed cysts posterior to the left atrium with compression of left upper pulmonary vein and an intraluminal cyst developing inside the left auricle.

In the right ventricle (RV), there was a cyst originating from the RV apex (Figure 2) with a regular contour superior to the diaphragm. Also, posterior to the right atrium there were multiple lobulated cysts with intraluminal development.

|

Figure 2: Cine bSSFP at end-diastole in an off-axis 4 chamber view. Along the posterior border of the LV, there are multiple cysts in the mediastinum (small arrows), and a large cyst originating from the RV apex (large arrow).

Conclusion:

After the CMR, there was a cardiac CTA performed using a GE OPTIMA CT660 scanner with a triple rule-out protocol. The scan utilized prospective ECG-gated acquisition to investigate potential causes of ECG abnormalities and shortness of breath, including coronary artery involvement and pulmonary embolism.

The results indicated multiple cardiac and pulmonary hydatid cysts of varying ages (classified as Gharbi 1 to 3) along with a chronic bilateral segmental pulmonary embolism without signs of pulmonary hypertension.

The cardiac CTA showed compression of superior vena cava (SVC) by two cysts (Figure 3), a ruptured cyst at the level of a lingular bronchus of the left upper pulmonary lobe, a cyst likely developing in the pleura at the apical segment of the left lower lobe, and a paravertebral cyst of pleural origin in contact with the descending aorta.

|

Figure 3: Cardiac CTA in sagittal projection showing compression of the SVC by two hydatid cysts near the entrance into the right atrium.

An intra-cystic course of the mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery (Figure 4), the mid left circumflex artery, and the first marginal were present. Also, a pre-cystic course of the distal LAD (Figure 5) along with the first diagonal artery were present.

|

Figure 4: Multiplanar reformat (MPR) of a cardiac CTA showing an intra-cystic course of a portion of mid-LAD and the first diagonal (arrows).

|

Figure 5: Maximum intensity projection (MIP) reformat of a cardiac CTA showing intra-cystic course of a portion of mid-LAD (arrow).

The compression of the SVC influenced the choice of cannulation for cardiac surgeons, leading to the adoption of a femoral cannulation. Additionally, the pulmonary veins were surrounded by numerous cysts without signs of congestion making it unlikely for them to be the main cause of symptoms. Following these diagnostic tests, the cardiac surgeons discussed the risks with the patient, who opted to undergo surgery. The surgical approach focused on evacuating daughter cysts and inner capsules from the larger cysts only. However, the procedure unfortunately led to refractory anaphylactic shock, resulting in the patient’s death.

|

Movie 5: Surgical view showing the extraction of a large cyst attached to the right atrium.

Perspective:

Cardiac hydatid cysts, although rare, present a significant medical challenge particularly in endemic regions where they are found in fewer than 2% of cases of hydatidosis. The disease can manifest in various ways, often involving multiple organs in approximately 50% of cases.[1] Diagnosis is critical, especially in patients with suggestive findings on CXR, as the growth of these cysts can lead to a range of complications affecting cardiac function and surrounding structures.[2]

Cardiac echinococcosis is encountered infrequently, with a prevalence ranging from 0.01% to 2%.[3] The heart’s natural contractions provide some resistance to viable hydatid cysts making primary echinococcosis of the heart a rare event.[4] While any part of the heart can be affected, the most common locations are the free wall of the LV and the interventricular septal wall, followed by the atria and intracavity area.[5,6]

Echocardiography serves as the cornerstone for diagnosing cardiac hydatidosis due to its ability to visualize typical cystic structures.[7] However, confirming the diagnosis may require additional imaging modalities (CT and CMR) and serologic tests for comprehensive evaluation. Distinguishing hydatid cysts from other cardiac pathologies, such as myxomas, underscores the importance of accurate diagnosis for appropriate management decisions.[8,9]

The clinical implications of cardiac hydatid cysts extend beyond the cardiovascular system with potential complications including pulmonary embolism, coronary artery compression, and life-threatening events such as anaphylaxis.[10] Surgical intervention remains the primary treatment modality often supplemented with Albendazole therapy to mitigate risks associated with cyst rupture and recurrence.[11] Early recognition and aggressive management are imperative given the potential for severe morbidity and mortality associated with untreated cases.

In conclusion, cardiac hydatid cysts represent a complex and challenging medical condition necessitating a multidisciplinary approach for accurate diagnosis and optimal management. Despite their rarity, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion in endemic regions to facilitate timely intervention and mitigate the risk of complications associated with this potentially life-threatening condition.

Click here to view the entire CMR on CloudCMR.

Click here to view the entire CT on CloudCMR.

References

- Bayazid O, Ocal A, Isik O, Okay T, Yakut C. A case of cardiac hydatid cyst localized on the interventricular septnm and causing pulmonary emboli. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1991;32:324–6.

- Gula G, Luisi VS, Machado F, Yacoub M. Hydatid cyst of the heart, clinical and surgical implications. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1979;27:393–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1096284.

- Maffeis GR, Petrucci O, Carandina R, Leme CA Jr, Truffa M, Vieira R. et al. Cardiac echinococcosis. Circulation. 2000;101:1352–4.

- Kabbani SS, Jokhadar M, Sundouk A, Nabhani F, Baba B, Shafik AI. Surgical management of cardiac eshinococcosis, report of four cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1992;33:505–10.

- Ugurlucan M, Sayin OA, Surmen B, Coppin M, Champsaur G. Images in cardiovascular medicine, Hydatid cyst of the interventricular septum. Circulation. 2006;113:869–70 7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595298.

- Tandon S, Darbari A. Hydatid cyst of the right atrium: a rare presentation. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2006;14:e43–4. doi: 10.1177/021849230601400324.

- Oliver JM, Sotillo JF, Domínguez FJ, López de Sá E, Calvo L, Salvador A. Two dimensional echocardiography feutures of echinococcosis of the heart and great blood vessel, clinical and surgical implications. Circulation. 1988;78:327–7.

- Jeridi G, Boughzala E, Hajri S, Hediji A, Ammar H. Complicated hydatid cyst of the right atrium simulating myxoma of the tricuspid valve. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 1997;46:159–62.

- Bolourian AA. Cardiac echinococcosis presenting as myxoma, report of very rare case. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:62–3.

- Karadede A, Alyan O, Sucu M, Karahan Z. Coronary narrowing secondary to compression by pericardial hydatid cyst. Int J Cardiol. 2008;123(2):204–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.174.

- Zebirate L, Bouchenafa S, Boukli Hacene AZ, Draou NE, Atbi M. 198 Clinical and radiological features of cardiac hydatid cysts: A case series. Br J Surg. 2023;110(Issue Supplement_7):September 2023, znad258.225.

Case prepared by:

Jeffrey M. Dendy, MD, FACC

Editorial Team, Cases of SCMR

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine