Othman Y. Bricha M.D, Vincent Sachs D.O, Dany Sayad M.D

USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL

Clinical History:

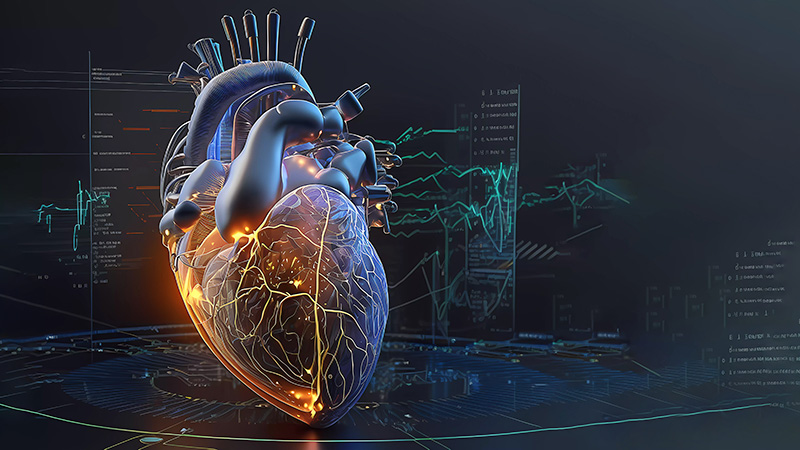

An 18 year old male with history of intussusception as a child, recurrent venous thromboembolism and recent viral myocarditis presented as a transfer from an outside facility for surgical evaluation of an incidentally discovered 4.4 cm x 6.5 cm x 5.5 cm left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysm after presenting with a 2 week history of exertional dyspnea and abdominal distention (Figure 1). His labs were significant for elevated liver enzymes, high sensitivity troponin of 64 ng/L (normal < 14 ng/L) and pro B-type natriuretic peptide of 717 pg/mL (normal <125 pg/mL). Chest computed topography (CT) angiography was negative for pulmonary embolism and CT abdomen and pelvis were notable for diffuse ascites but otherwise no acute complications.

Review of outside medical records were notable for two previous visits with cardiac abnormalities. The first presentation involved an emergency room visit approximately 6 months prior, after a motor vehicle collision with complaints of mild neck, chest and abdominal pain. Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and he demonstrated elevated high sensitivity troponin of 306 ng/L (normal < 14 ng/L). A bedside thoracic ultrasound was performed, and reported good ventricular motion, with no effusion or mention of apical abnormalities. He subsequently underwent CT of head, spine, chest, abdomen and pelvis which were all negative for acute processes. Cardiology was consulted who recommended admission and 2D echocardiogram, but the patient and father elected to leave against medical advice. Furthermore, the family reported a history of viral myocarditis diagnosed 4 months prior that was treated conservatively with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. It is unclear whether 2D echocardiogram or cardiac biomarkers were obtained at the time as these records were not available for review. Nonetheless, the patient notes his pleuritic chest pain had spontaneously resolved.

At the time of initial presentation to our hospital, the patient was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, tachypneic (RR 30) secondary to abdominal distension. Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and repeat high sensitivity troponin was 23 ng/L (normal < 14 ng/L). Right heart catheterization was performed in anticipation for surgical optimization which showed reduced cardiac index (1.8L/min/m2) in the setting of hypovolemia, normal PA pressure (13/5 mmHg) and preserved right ventricular (RV) systolic function. Review of outside CT images with our radiologist confirmed the findings of a 4.4 cm x 6.5 cm x 5.5 cm LV pseudoaneurysm. A cardiac magnetic resonance study was ordered to better define the pseudoaneurysm prior to surgical intervention.

Figure 1. Transthoracic echocardiogram apical four chamber view. There is a large left ventricular apical pseudoaneurysm present. |

CMR Findings:

CMR performed on a 1.5 T GE Signa Artist scanner to assist in surgical planning for repair. The techniques performed are as follows: Steady-state free precession cine imaging in multiple imaging planes, gadolinium contrast enhanced first-pass myocardial perfusion imaging at rest, velocity-encoded phase-contrast imaging in multiple image planes for blood flow quantification, T2-weighted triple-inversion recovery fast-spin echo imaging in multiple imaging planes.

CMR was most notable for a large, 6 x 4.3 cm LV apical pseudoaneurysm, that contains blood without definitive evidence of thrombus (Movies 3-7). The LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was 58 % by summation of disc method and global LV function was normal. Aside from the apical cap, there were no regional wall motion abnormalities of the LV wall. There was no evidence of myocardial edema by T2 weighted imaging. Furthermore, there was resting first-pass myocardial perfusion defect at the apex at the origin of the pseudoaneurysm (Movie 8), with no late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) involving the LV myocardium. Lastly, the global RV function was normal, with no regional wall motion abnormalities or LGE involving the RV wall.

Movies 3-6: Cine SSFP in the 2 chamber, 4 chamber, 3 chamber, and apical short axis views. There is a large pseudoaneurysm arising from the left ventricular apex with normal bi-ventricular systolic function. |

Movie 7. Axial 3D SSFP. There is a large left ventricular pseudoaneurysm and large right pleural effusion present. |

Movie 8. Four chamber perfusion. Large left ventricular apical pseudoaneurysm present with contrast entering the pseduoaneurysm from the entrance of a defect in the apical inferior wall. |

Conclusion:

Under our care, the patient underwent hepatology and hematologic workup in preparation for surgical intervention. Hepatology workup was notable for pattern of Budd Chiari syndrome (portal vein thrombosis) with no fibrosis or cirrhosis. We suspect the stasis occurring in the hepatic venous system contributed directly to the abdominal ascites and the hepatic hydrothorax presented in the form of a pleural effusion of the right lung base. Hypercoagulable workup was largely unremarkable (including negative for PNH and JAK2) and the etiology of his deep venous thrombosis history remains unclear.

He subsequently underwent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure to offload hepatic congestion and was taken to the operating room with cardiothoracic surgery for repair. Per the operative note, the patient underwent a full sternotomy allowing complete view of the pericardium and the capsule of pseudoaneurysm was then partially excised and the perforation was closed with a double layer prolene suture. Samples of the aneurysm were sent down for pathology and it was largely unremarkable showing benign fragments of fibrous tissue with chronic inflammation fibrin deposition and hemorrhage consistent with pseudoaneurysm.

Transesophageal echocardiogram confirmed no residual leak and preserved ejection fraction after the procedure. Follow-up 2D echocardiogram was obtained post-operatively and showed LVEF of 60-65% with no regional wall motion abnormalities or evidence of pseudoaneurysm (Figure 2). The patient’s post-operative course was uncomplicated, and he was eventually discharged from the hospital to home with close follow up.

Figure 2. Transthoracic echocardiogram apical four chamber view. There is no left ventricular apical pseudoaneurysm or pericardial effusion present. |

Perspective:

LV pseudoaneurysms are a rare entity and are often associated with cardio-thoracic surgery or myocardial infarctions.[1,2] Although the pathophysiology is not entirely clear, it is thought that focal weakening in myocardial tissue results in outpouching of pericardial tissue.[2] Our patient presented with a unique combination of trauma, viral myocarditis and hypercoagulable state which we suspect synergistically contributed to the formation of his large pseudoaneurysm. Our patient had not undergone any procedures that could lead to iatrogenic injury such as cardiac catheterization. Although we are unable to fully ascertain causation, we can speculate that the findings of a LV pseudoaneurysm were not congenital as this patients’ history of chronic hypercoagulability resulted in extensive medical care from an early age. After reviewing the literature, our case appears to be one of the first possible descriptions of a late mechanical complication that presented 8 months post cardiac contusion.

CMR imaging is a useful imaging modality that allows for better characterization of many mechanical complications, especially pseudoaneurysms. Upon initial presentation to our service, there was concern whether the 2D echocardiogram findings were demonstrating a pseudoaneurysm vs true aneurysm. CMR imaging was obtained to better classify the 2D echocardiogram findings and assist our cardio-thoracic surgeons in their approach.

Of note, many different imaging modalities were initially obtained in the diagnostic workup of our patient including an x-ray and CT scan of the chest.[3] Chest x-ray is a relatively inexpensive exam that is most sensitive for old pseudoaneurysms that have calcified over time.[3] CT scans are a more sensitive and specific imaging modality for pseudoaneurysms that allow detection of the aneurysm in multiple different axis.[3] Lastly, 2D echocardiogram and CMR imaging are the two mainstay imaging modalities regarding intra-cardiac pathology that can be used in conjunction to evaluate both cardiac function and structure.[3]

Pseudoaneurysms could present as a late complication of post cardiac contusion and clinicians should be aware of this possibility. CMR is a robust imaging modality that can be used to investigate mechanical pathologies. Lastly, surgical optimization in preparation for surgery is of the utmost importance upon a patient’s initial presentation.

Click here to view the images on CloudCMR.

References:

- Inayat F, Ghani AR, Riaz I, Ali NS, Sarwar U, Bonita R, Virk HUH. Left Ventricular Pseudoaneurysm: An Overview of Diagnosis and Management. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018 Aug 2;6:2324709618792025. doi: 10.1177/2324709618792025. PMID: 30090827; PMCID: PMC6077878.

- Prêtre R, Linka A, Jenni R, Turina MI. Surgical treatment of acquired left ventricular pseudoaneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Aug;70(2):553-7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01412-0. PMID: 10969679.

- Brown SL, Gropler RJ, Harris KM. Distinguishing left ventricular aneurysm from pseudoaneurysm. A review of the literature. Chest. 1997;111(5):1403-1409. doi:10.1378/chest.111.5.1403

Case prepared by:

Madhusudan Ganigara, MD

Editorial Team, Cases of SCMR

The University of Chicago, Department of Pediatric Cardiology

Chicago IL