Amol Anil Kulkarni1, DNB, Darshan Chudgar1, DNB, Nitin J Burkule2, MD, DM

Department of Radio Diagnosis1, Department of Cardiology2, Jupiter Hospital, Thane, Maharashtra, India

Clinical History

A 5-year-old female child born by a third-degree consanguineous marriage was extensively evaluated for concerns of short stature at the age of 1 year. Genetic work up showed homozygous base pair deletion in exon 19 (c.2055_2059), a pathogenic variant of the TRIM 37 gene which is diagnostic of Mulibrey nanism. She was initiated on growth hormone therapy.

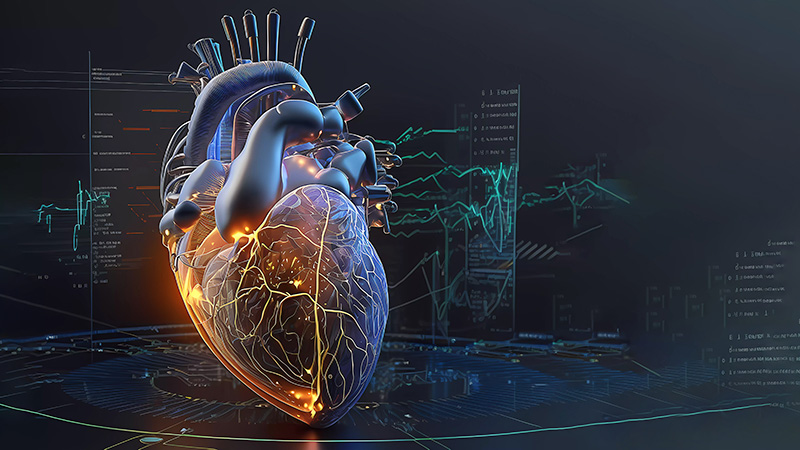

The child was on regular monitoring and over the last 4-5 months developed abdominal discomfort. Laboratory tests showed elevated ALT (58U/L; normal <35 U/L), AST (70 U/L; normal <35 U/L), GGT (85 U/L; normal <50 U/L), ALP (351 U/L; normal 97–296 U/L), and mild proteinuria (Urine protein 81.13mg/dL, normal <14 mg/dL). NT-proBNP was 494 pg/mL (normal range <125 pg/mL) and reduced to 100 pg/mL after enalapril and diuretics. A liver biopsy was performed, which showed changes of congestive hepatopathy (Fibrosis score 2A). The abdominal ultrasound and echocardiographic assessments raised the suspicion of raised right heart filling pressures. The pericardial thickness on a gated contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) was normal ~ 1.5 mm, without any effusion or contrast enhancement (Figure 1). This prompted referral for further comprehensive cardiovascular evaluation to differentiate between pericardial constriction and restrictive cardiomyopathy, particularly in the context of Mulibrey nanism which is known to be associated with pericardial and myocardial fibrosis.

At the time of presentation, the patient was alert and cooperative, showing no signs of respiratory distress. Vital signs revealed a heart rate of 106 beats per minute with a regular, good-volume pulse that was symmetrical in all limbs, and an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. Anthropometric measurements indicated a height of 87 cm and weight of 8.4 kg, both below the 3rd percentile for age, suggestive of short stature and failure to thrive. Jugular venous pressure was elevated with a prominent y descent, but there was no lower limb oedema. On precordial examination, heart sounds were normal with no added sounds or murmurs. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed T-wave inversion in leads V1 to V4 and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), with no evidence of atrial enlargement and a normal QRS axis (Figure 1).

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60%, global longitudinal strain (GLS) of -18.6%, and valvular function. TTE also showed normal right ventricular (RV) function (RV free wall strain -20%, S’ 10 cm/s). Features of constrictive physiology were seen with inspiratory leftward septal shift (Movie 1), >30% reciprocal respiration phasic variation in mitral and tricuspid inflow velocities, annulus reversus on tissue Doppler (Figure 2), congested inferior vena cava (IVC) with no respiratory variation in diameter (Movie 2), hepatic vein expiratory diastolic reversal/forward flow >>1 (Figure 3), and >30% pulsatility in portal venous flow.

|

| Figure 1. (A) Axial section from an ECG gated cardiac CT showing normal thickness pericardium measuring up to 1.5 mm. No abnormal pericardial thickening, enhancement or effusion is observed. (B) 12 lead ECG showing normal sinus rhythm, T inversion in leads V1-V4 consistent with juvenile pattern. |

|

| Movie 1. 2D TTE parasternal short axis cine showing inspiratory leftward septal shift. |

|

| Figure 2.(A) Respiratory variation of mitral flow pulse wave spectral Doppler showing an inspiratory reduction and expiratory increase in mitral flow (yellow arrows). (B) Respiratory variation of tricuspid flow pulse wave spectral Doppler showing an inspiratory increase and expiratory reduction in tricuspid flow (yellow arrows). (C) Lateral mitral annular tissue Doppler E’ = 11 cm/sec. (D) Medial mitral annular tissue Doppler E’ = 12 cm/sec (annulus reversus). |

|

| Movie 2. 2D TTE sub-costal view showing severely congested IVC and hepatic veins without any respiratory variation in IVC diameter. |

|

| Figure 3. Hepatic venous flow pulse wave spectral Doppler pattern suggestive of pericardial constriction. The first heartbeat in expiration shows that the diastolic forward flow (D wave) is less than systolic forward flow (S wave) with late diastolic flow reversal / diastolic forward flow ratio > 1 (yellow arrows). In inspiration, D>S with late diastolic flow reversal / diastolic forward flow ratio <0.5 (green arrows). |

Cardiac catheterisation showed near equalisation of diastolic filling pressures [mean right atrial (RA) pressure 16 mmHg, right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP) 18 mmHg, left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) 18 mmHg] and pulmonary hypertension (PH) (pulmonary artery pressures: systolic 40 mmHg, diastolic 16 mmHg, mean 27 mmHg).

CMR Findings

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed on a 1.5-T Altea scanner (Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany). Gadolinium-based contrast agent was used in a concentration of 0.2 mmol/kg of body weight. Both the left ventricle (LV) and RV were normal in size, morphology, and function, with preserved systolic function (LVEF 56% and right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF 62%). No LVH was seen (LV mass = 12g, Z score -0.81). No fatty infiltration was observed. LV GLS was measured from cine balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) images using SuiteHeart software (NeoSoft, Pewaukee, WI, USA). Normal GLS range for this age group is approximately -17% to -23% (Echocardiography based Z scores available at Boston Children’s Hospital) (Figure 4, Movie 3).

|

| Figure 4. Still frames from a real time non-triggered free breathing cine gradient recalled echo (GRE) acquisition at end expiration and early inspiration showing early diastolic leftward septal shift (flattening) during the early phase of inspiration. |

|

| Movie 3. Mid short axis real time non-triggered free breathing cine GRE acquisition showing early diastolic leftward septal shift (flattening) during the early phase of inspiration. |

Myocardial tissue characterization showed native T1 value of 969 +/- 60 ms (normal adult range 1100 +/- 50 ms) and T2 value of 52 +/- 5 ms (normal adult range 53 +/- 6ms) (Figure 5), and no myocardial delayed enhancement, indicating the absence of fibrosis or inflammation. The CMR characterisation of myocardium (mass, GLS, T1, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)) ruled out restrictive myocardial disease.

The pericardium appeared morphologically normal, with a maximum thickness of 1.5 mm (Figure 5) on T1 Turbo spin echo axial images, and no evidence of pericardial effusion or LGE (Figure 5). Both atrial size was at upper limits for normal (LA volume = 14.3 mL, Z score 1.64). The mitral and tricuspid valves demonstrated normal function without regurgitation.

|

| Figure 5. Tissue characterisation on CMR. (A) Mid short axis native T1 map shows normal myocardial T1 values. (B) Mid short axis T2 map shows normal myocardial T2 values. (C) Axial T1 weighted turbo spin echo image showing normal pericardial thickness of 1.5 mm. (D, E, F) Basal, mid, apical short axis phase sensitive inversion recovery images showing no myocardial or pericardial LGE. |

Conclusion

In this case of Mulibrey nanism, CMR played a pivotal role in diagnosing constrictive physiology with normal pericardial thickness and ruling out restrictive cardiomyopathy. Cine imaging demonstrated early inspiratory septal flattening, hallmark of ventricular interdependence, which strongly supported the diagnosis of pericardial constriction. Notably, pericardial thickness was within normal limits, and there was no pericardial effusion or LGE consistent with the case series in the literature reporting normal pericardial thickness in these patients undergoing surgical pericardiectomy. Myocardial tissue characterisation revealed normal mass, normal GLS, normal native T1 and T2 values, and no LGE, effectively ruling out isolated or concomitant restrictive cardiomyopathy.

In view of the clinical and imaging signs of pericardial constriction, raised NT-proBNP along with imaging and biochemical evidence of congestive hepatopathy, a decision was made to proceed with pericardiectomy. The pericardium appeared normal in thickness during surgery and a complete pericardiectomy was successfully achieved.

Follow-up TTE and CMR were performed three months post pericardiectomy. 2D TTE and Doppler study showed normal IVC size with >50% respiratory variation (Movie 4), normalization of hepatic venous Doppler waveforms (Figure 6). CMR showed significantly reduced, although mildly persistent, inspiratory leftward septal shift, indicative of favourable post-surgical relief of constriction and clinical recovery (Movie 5).

|

| Movie 4. Post pericardiectomy 2D TTE sub-costal view showing no IVC or hepatic veins congestion. The IVC shows normal inspiratory collapse. |

|

| Figure 6. Post pericardiectomy TTE normalisation of hepatic venous flow pulse wave spectral Doppler. The first heartbeat in expiration shows normalization of flows with S=D with diastolic flow reversal / diastolic forward flow ratio <0.5 (yellow arrows). In inspiration D>S without diastolic flow reversal (green arrow). |

|

| Movie 5. Post pericardiectomy mid short axis real time non-triggered free breathing cine GRE acquisition showing significantly reduced, although mildly persistent, inspiratory leftward septal shift. |

This case highlights that in children with Mulibrey nanism constrictive physiology can be present with normal thickness pericardium. These patients have highly collagenised and poorly elastic pericardium. The grown-up children of Mulibrey nanism may also have concomitant myocardial fibrosis. Before proceeding with pericardiectomy it is mandatory to rule out the dominant component of myocardial restriction using advanced multimodality cardiac imaging.

Perspective

Mulibrey nanism (Muscle–Liver–Brain–Eye nanism) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the TRIM37 gene, which encodes a peroxisomal protein of the RING-B-box-coiled-coil family [1]. The condition is characterised by severe prenatal-onset growth failure and multisystem involvement, affecting the cardiovascular, skeletal, hepatic, endocrine, and ophthalmic systems.[1] While sporadic cases have been documented worldwide, Mulibrey nanism shows marked geographic clustering in Finland, where approximately 85 of the ~110 reported cases originate.[1]

Cardiac manifestations are a major determinant of morbidity and mortality, with more than 50% of patients developing congestive heart failure (CHF) during their lifetime.[2] The classic cardiac phenotype comprises constrictive pericarditis, LVH, and mild myocardial fibrosis, often with preserved systolic function but impaired diastolic compliance.[2,3] Histopathological studies have documented pericardial fibrosis and adhesions, and in some cases calcification.[2] However, advanced imaging, particularly MRI, has shown that pericardial thickness is often normal (<3–3.4 mm) even in patients with clear constrictive physiology, including those who have undergone pericardiectomy.[4,5] The pathophysiology of heart failure presentation is not solely related to pericardial thickness but may be related to visceral pericardial fibrosis and additional myocardial structural-functional abnormalities, resulting in a constriction–restriction overlap.[3,6]

Recent paediatric TTE studies confirm that pericardial constriction in Mulibrey nanism is frequently functional, without imaging evidence of gross thickening.[3] Characteristic non-invasive findings include septal bounce, exaggerated respiratory variation in transvalvular flows, and reduced IVC collapse.[3] Mild biventricular systolic dysfunction and persistent diastolic abnormalities have been observed in some patients, even after pericardiectomy, underscoring the role of intrinsic myocardial disease.[3] These data support a comprehensive diagnostic approach combining TTE, respiratory cine CMR, and when indicated, invasive hemodynamic assessment.

Pericardiectomy remains the mainstay of treatment for haemodynamically significant constriction and can be effective even in patients without overt pericardial thickening, provided that functional evidence of constriction and clinical compromise are present.[2] In the largest and long-term follow-up series, approximately two-thirds of operated patients derived lasting benefit, while one-third had persistent or recurrent CHF due to myocardial restriction.[2] Delaying surgery, particularly beyond a decade from symptom onset, is associated with poorer outcomes, as irreversible myocardial, hepatic and gastrointestinal changes (cardiac cirrhosis and protein-losing enteropathy) may develop.[7,8] Early surgical intervention in presence of definitive constrictive physiology, no myocardial restriction and no congestive end-organ damage, appears to improve long-term mortality and morbidity.[8]

Click here for a link to the entire CMR on CloudCMR (Pre-surgical)

Click here for a link to the entire CMR on CloudCMR (Post-surgical)

References

- Karlberg N, Jalanko H, Perheentupa J, Lipsanen-Nyman M. Mulibrey nanism: clinical features and diagnostic criteria. J Med Genet. 2004;41(2):92-98.

- Lipsanen-Nyman M, Perheentupa J, Rapola J, Sovijärvi A, Kupari M. Mulibrey heart disease: clinical manifestations, long-term course, and results of pericardiectomy in a series of 49 patients born before 1985. Circulation. 2003;107(22):2810-2815.

- Sarkola T, Lipsanen-Nyman M, Jalanko H, Jokinen E. Pericardial constriction and myocardial restriction in pediatric Mulibrey nanism: a complex disease with diastolic dysfunction. CJC Open. 2022;4(1):28-36.

- Kokki S, Lauerma K, Kupari M, Lipsanen-Nyman M, Hekali P. Assessment of mulibrey nanism cardiopathy with functional magnetic resonance imaging. MAGMA. 2000;11(1-2):84-86.

- Kivistö S, Lipsanen-Nyman M, Kupari M, Hekali P, Lauerma K. Cardiac involvement in Mulibrey nanism: characterization with magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6(3):645-652.

- Eerola A, Pihkala JI, Karlberg N, Lipsanen-Nyman M, Jokinen E. Cardiac dysfunction in children with Mulibrey nanism. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28(2):155-162.

- Kumpf M, Hämäläinen RH, Hofbeck M, Baden W. Refractory congestive heart failure following delayed pericardectomy in a child with Mulibrey nanism due to a novel mutation in TRIM37. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(8):1141-1145.

- Sanchez AC, Vasigh M, Carhart R. The importance of early pericardiectomy in Mulibrey nanism syndrome: a case report. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2022;10:23247096221077816.

Case Prepared by:

Madhusudan Ganigara, MD

Cases of SCMR, Editorial team

Division of Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics

The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL