Shafkat Anwar MDa,d, Michael J. Bunker MSd, Eric W. Lam PhDb,e, Alexis Dang MDc,d

aDepartment of Pediatrics. bDepartment of Biochemistry and Biophysics. cDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery. dCenter for Advanced 3D+ Technologies (CA3D+).

eKAVLI-PBBR Fabrication and Design Center (FAD).

University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is taking a tremendous toll on the global population and healthcare systems. As of April 26 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports 2,810,325 cases globally, including 193,8251. In the United States of America (USA), there have been 859,766 cases with 50,439 deaths2 as of April 24, 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed several deficiencies within healthcare systems. Key problems hampering the COVID-19 response have been limited testing supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers (HCW), and ventilators for patients. As frontline HCWs and researchers work under these challenging conditions, innovators have rapidly pivoted to 3D printing (3DP) technologies as a response. 3DP enables flexible design, rapid prototyping and manufacturing – critical factors to meet sudden, unpredicted surges in demand.

The following is a summary of the landscape of 3D printing in healthcare in response to the COVID-19 crisis. This is a rapidly evolving field with innovations emerging daily, and as such any summary may approach obsolesce in short order. Thus, our goal is to provide an overview of pertinent applications and regulatory information to-date, as well as the primary source resources that will aid the reader stay up-to-date on this topic.

1. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and 3D printing for COVID-19

The FDA’s answers to frequently asked questions (FAQ) for entities who 3D print devices, accessories, components, and/or parts during the COVID-19 emergency:

https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/3d-printing-medical-devices/faqs-3d-printing-medical-devices-accessories-components-and-parts-during-covid-19-pandemic

FDA Enforcement Policy for Face Masks and Respirators for CODIV-19:

https://www.fda.gov/media/136449/download

While it may be technically possible to produce some 3D printed PPE, it is vitally important to recognize the limitations of 3D-printed solutions. For example, for surgical masks and respirators the FDA notes:

“3D-printed PPE may provide a physical barrier, but 3D-printed PPE are unlikely to provide the same fluid barrier and air filtration protection as FDA-cleared surgical masks and N95 respirators. The CDC has recommendations for how to optimize the supply of face masks.”

2. FDA, NIH, VA and public-private partnerships:

To harness the capacity of the capacity of the 3D printing industry, the FDA has entered a collaboration with Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Innovation Ecosystem and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 3D Print Exchange and the additive manufacturing (AM) organization America Makes. The goal of this collaboration is to connect stakeholders, facilitate information-sharing and process Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Applications to make available medical devices in response to COVID-19 crisis.

i. NIH 3D print exchange

A curated collection 3D printing designs in coordination with the FDA, VA, and America Makes to connect healthcare providers and 3D printing organizations:

https://3dprint.nih.gov/collections/covid-19-response

ii. US Dept of Veterans Affairs (VA) Innovation Ecosystem

Dep’t of VA 3D printing, design sharing, feedback and testing resource:

https://myvapm.force.com/3DPrintingNew/s/

iii. America Makes

America Makes is the Department of Defense’s Manufacturing Innovation Institute (DoD MII) for additive manufacturing. America Makes is comprised of member organizations across government, academic and private sectors to accelerate additive manufacturing.

3. 3D Printed solutions in Response to the COVID-19 Crisis

The following is a sample of solutions to date. We are highlighting 5 solutions for the healthcare setting, realizing there are many more in various stages of development.

We have prioritized solutions that have received emergency use authorization (EUA) from the FDA, or are FDA-exempted. This is not a comprehensive list, and the reader is encouraged to reference the NIH 3D Print Exchange website above for more information. Inclusion of these solutions in this publication does not constitute an endorsement of these products. The reader is advised to independently ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of these designs.

i. 3D Printed Face Shield

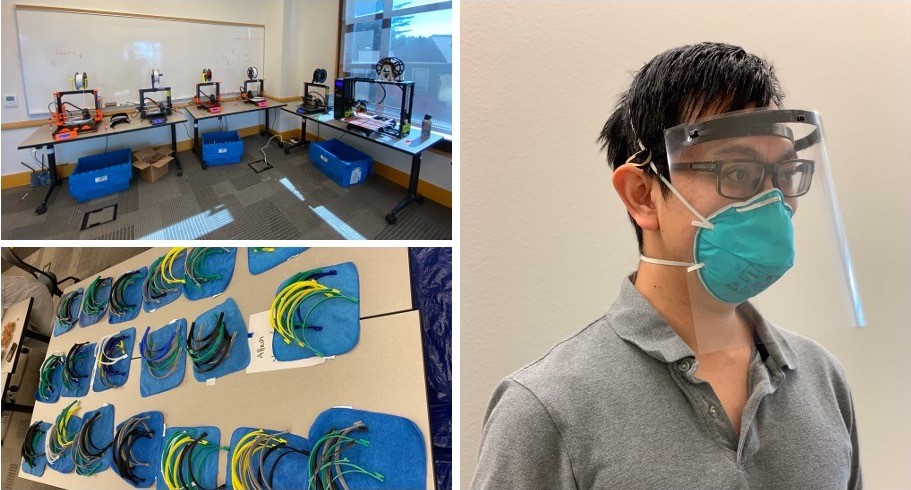

The design for the UCSF 3D Shield was inspired by the Prusa RC2 model, with modifications. The UCSF face shield uses an 8.5”x11” transparency sheet which is readily available and mounted after a simple 3-hole punch. The user puts on the face shield using interlinked rubber bands, which are replaceable as needed and easy to source. They are printed on FDM printers, are low cost, and at a capacity of 300+ shields a day by a team of volunteers at the UCSF library.

https://www.library.ucsf.edu/news/ucsf-3d-printed-face-shield-project/

Figure 1: UCSF Face Shields project. Left panels: 18 3D printers producing face shields. Right panel: Dr. Alexis Dang wears an assembled face shield over an N-95 respirator

ii. 3D Printed Surgical Face Mask

According to the designers, “The Stopgap Face Mask (SFM) was created as an emergency action in effort to protect people by providing backup PPE options if the standard PPE has become unavailable.” The mask uses 3D-printed components that houses filter material from a conventional face mask.

https://3dprint.nih.gov/discover/3dpx-013429

As one conventional face mask can it up to four SFMs the potential value-add of the device is to augment the supply of standard surgical face masks if times of shortage. It should be noted that this device is NOT an N95 respirator. The device is printed on a Multi-Jet Fusion (MJF) or Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) printer out of powder-bed nylon, and has received EUA from the FDA.

iii. Nasal Swabs

Widespread COVID-19 testing is one of the critical factors to successfully counter this pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends collecting and testing an upper respiratory specimen from a nasopharyngeal (NP) swab-based sample3. However, a shortage of specialized NP swabs is one of the factors hampering widespread testing. 3D printed NP swabs have been developed to rapidly augment the existing supply. A consortium of collaborators from industry and academia have identified several 3D printed swabs for use in COVID-19 testing. The consortium includes the academic institutions Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Stanford University; the University of South Florida; and the University of Washington, and industry partners Carbon and Resolution Medical, EnvisionTEC, FormLabs, HP, OPT Industries and Origin.

https://www.bidmc.org/about-bidmc/news/2020/04/3d-printed-swabs

A clinical trial by this consortium has identified four novel prototypes of 3D-printed swabs that can be used for COVID-19 testing. A preprint of the manuscript is available

here: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.14.20065094v1

Examples of these NP swabs are available here:

https://www.carbon3d.com/covid19/

https://formlabs.com/covid-19-response/covid-test-swabs/

https://www.origin.io/npswab/

iv. 3D Printed ventilator expansion device

The COVID-19 crisis has been marked by a shortage in the supply of ventilators to deliver critical support. 3D printing has been applied to create adapters that increase the capacity of ventilators to support more than one patient. One example is from Prisma Health, which has received emergency use authorization from the FDA for VESper™. This device that allows one ventilator to support up to two patients during times of acute ventilator shortages. Details here: https://www.prismahealth.org/VESper/

v. 3D printed Door Handles

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for COVID-19, can remain infectious on solid surfaces for up to 72 hours4. To mitigate viral transmission via the contact route, “hands-free” handles have been rapidly prototyped and 3D printed. These handles allow users to open doors without using a hand to grasp the door handle. These are technically not medical devices and thus do not fall within the purview of FDA regulation. However, users should check with their institution’s internal groups prior to installing. These “devices” may require clearance from the safety and accessibility standpoints, which include stress testing fire-safety clearance, and compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards. A few examples are shown here:

UCSF 3D Printed Door Opener

https://ucsf.box.com/s/d2uos6twtl46styjogyjstcsx6zviggb

Materliase 3D Printed Door Opener

https://www.materialise.com/en/hands-free-door-opener

4. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating consequences on human health and well-being, while severely straining the health care industry and traditional supply chains. 3D printing and rapid prototyping technologies have allowed innovators, healthcare workers and researchers the ability to quickly create solutions to tackle some of these problems. While 3D printing technology is now ubiquitous and more accessible than ever before, most 3D printed solutions currently exist outside the bounds of traditional FDA and other regulatory-body testing. Therefore, caution must be exercised when implementing these new solutions in the clinical environment. At the same time the COVID-19 crisis has united academic, healthcare and industry partners to collaborate on an unprecedented scale. This shall likely have a lasting positive effect on healthcare in the era post- COVID-19.

References

Please reference the links above, and:

1. World Health Organization COVID-19. https://covid19.who.int/

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens from Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html

3. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with

SARS-CoV-1

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2004973#readcube-epdf