Case from: Vincent L Sorrell, Naser Mahmoud, Majid Asawaeer

Institution: University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

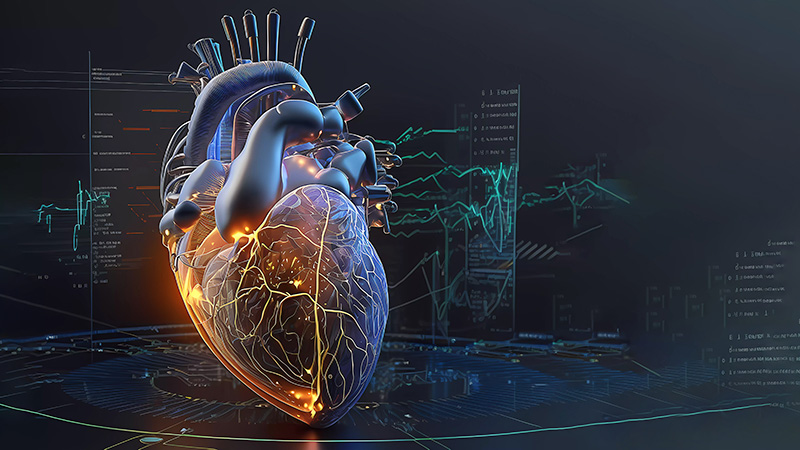

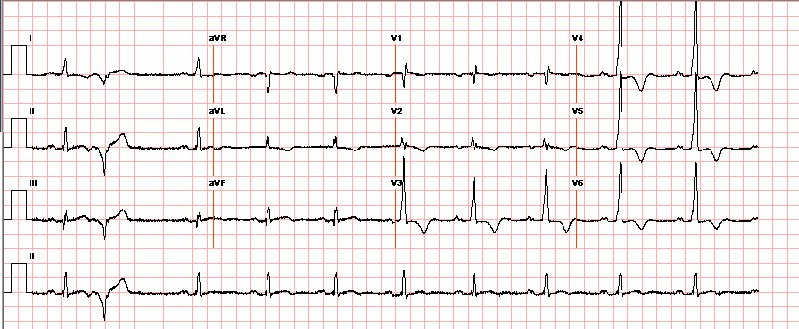

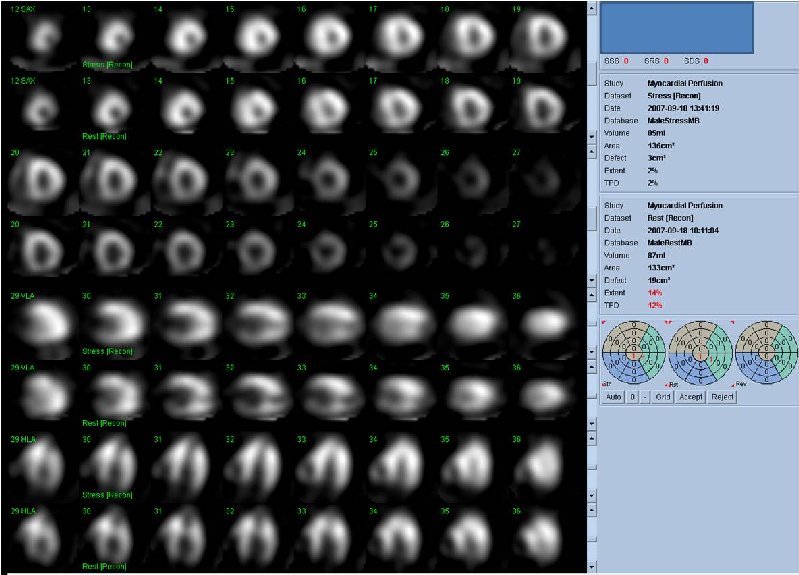

Clinical history: An 63 year old male initially presented to the outpatient clinic with fatigue and progressive shortness of breath. A resting electrocardiogram (ECG) showed tall R waves and giant negative T waves in the precordial leads (figure 1). Labs were performed, an echocardiogram was requested to evaluate LV function, and a nuclear SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging study performed for suspected myocardial ischemia (Movies 2 and 3). Blood work confirmed hypothyroidism. Echo revealed a large pericardial effusion and hypertrophied LV walls – possible HCM. The nuclear scan was negative for ischemia, but surprisingly revealed a fixed perfusion defect in the LV apex.

Fig 1 :Precordial leads from 12 lead ECG demonstrate tall QRS pattern with high r-wave and deep t-wave inversions. This pattern is common for apHCM and warrants consideration for this disease, but may also be found in myocardial ischaemia, infarction, ventricular hypertrophy (‘strain’ patterns), and even elevated intracranial pressure.

At this point, the referring physician questioned the data, and asked to perform a cardiovascular MRI (CMR) to confirm which test is accurate (the ‘normal echo’ wall motion or the ‘apical scar’ nuclear stress test). This has become a common approach to the use of CMR, but in this author’s opinion, is neither cost-efficient nor sustainable given healthcare cost concerns.

Movie 2A: 2D echocardiogram; parastenal long-axis orientation. A large pericardial effusion is noted. There is biventricular hypertrophy with normal LV (and RV) contraction. The apex is seen in this view (which should raise suspicion for apHCM).

Movie 2B: 2D echo; apical 4-chamber view. Interpretation stated “normal global LV function and pericardial effusion. No wall motion abnormality.” Although not recognized by the interpreting physician, the apical portion of both LV and RV suggest apHCM. No apical aneurysm is seen.

Figure 3A. Rest and stress myocardial SPECT MPI using Tc99m (gray scale). A focal defect is seen in both stress (top row) and rest (bottom row) of images.

Movie 3B. Rest and stress myocardial SPECT MPI using Tc99m (color display). A focal defect is again seen in both stress (top row) and rest (bottom row) of reconstructed bulleyes display and the rotating 3D images.

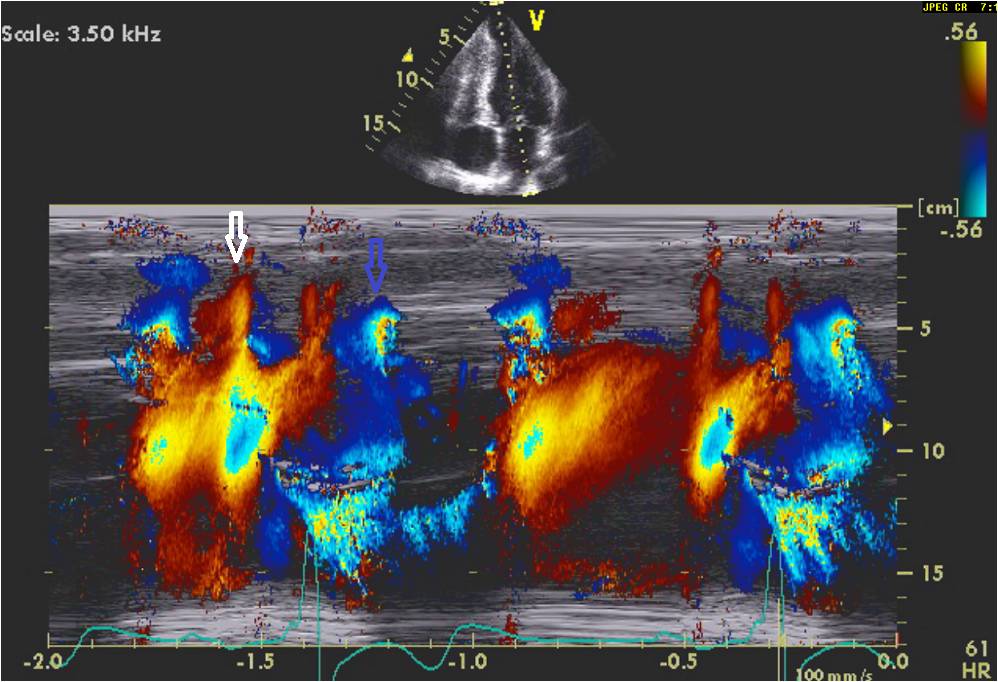

CMR Findings: Prior to performing the CMR, we chose to review each of the already completed exams for quality and accuracy. Despite the ‘normal-appearing’ apical wall motion on conventional apical 4-chamber views, off-axis views could demonstrate the LV apical scar on the original echo data (Movie 4). A mid-LV gradient could also be demonstrated on color flow Doppler. Color M-mode is able to clearly demonstrate the timing of this diastolic LV apical gradient phenomenon (Figure 4C). To optimally characterize the LV scar and extent of myocardial fibrosis, the CMR was performed (Figure 5). After treatment for hypothyroidism, a repeat echocardiogram confirmed the resolution of the pericardial effusion and clearly demonstrated the LV apical aneurysm (Movie 6). CMR confirmed the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, apical variant (apHCM), with the presence of an apical aneurysm and associated transmural scar.

Movie 4A. 2D echo, apical 4-chamber orientation. Slight inferior tilt of the transducer clearly demonstrates the previously hidden apical aneurysm (with suspected apical thrombus – echo-bright structure). Note the regional wall thickening of both ventricular apices.

Movie 4B. 2D echo, A4C, inferior tilt, with color flow Doppler. Note the “to-and-fro” (systolic and diastolic) color mosaic as flow accelerates (confirming a gradient) both into (diastolic) and out of (systolic) the apex during both phases of the cardiac cycle.

Figure 4C: Color M-mode nicely demonstrates the timing of these events shown in figure 4B. Note that the diastolic component (white arrows) is much more focused in the apical region than the systolic (blue arrows) gradient.

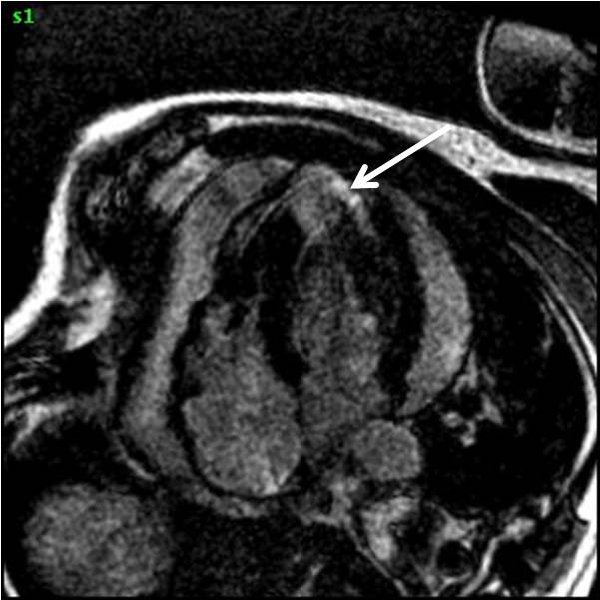

Figure 5B (movie). CMR, steady state free precession cine image, short-axis, mid-ventricular orientation. A large pericardial effusion is again seen. Systolic cavity obliteration (the cause of the ventricular gradient) is well shown. Also seen is the dramatic ‘cardiac rotation’ [counterclockwise] that is measured using ‘twist’ and ‘torsion’ parameters (not performed on this study).

Figure 5C. CMR, post-contrast LGE series. Although image quality was suboptimal (PVC’s and limited breath-hold cooperation), it was still able to demonstrate a definite region of focal transmural myocardial enhancement (arrow).

Movie 6: 2D echo; apical 4-chamber orientation. Note the pericardial effusion has resolved, the LV apical aneurysm is more prominent, and the RV apex now also appears to have dyskinetic motion suggesting the early development of a similar RV apical aneurysm.

Conclusion: .ApHCM is found in 3% of patients with HCM in the US population and is characterized by localized apical hypertrophy1. Development of a focal LV apical aneurysm is associated with intraventricular thrombosis and life-threatening arrhythmias, and therefore, unlike the normally ‘benign’ apHCM, carries a poor prognosis.2,3 The incidence of apical aneurysm formation is not uncommon and has been reported to be 10% – 20%4. This finding carries an annual cardiovascular mortality of 0.1% and an overall survival or 95% at 15 years5.

The underlying pathophysiology of apical HCM and apical aneurysm formation is not known. It is suspected that sustained relative ischemia (ie, mismatch between blood supply and the increased oxygen demand of the severely hypertrophied apical myocardium) might represent a pathogenic factor in the formation of fibrotic tissue and aneurysm formation6. A recent case report in SCMR COTW Number 11-04 “One question with two answers,” concluded that the increase in the apical wall thickening was associated with microvascular dysfunction and mid-wall fibrosis formation, whereas the macrovascular disease (CAD) resulted in localised infarction with peri-infarct perfusion defect in the territory of the affected coronary artery.

CMR provides a single tool to delineate the diagnosis and the prognosis of patients with apHCM. We believe it may help in stratifying patients who need further invasive procedures (eg. SCMR COTW Number 11-04) versus those who require only conservative care (eg. this case).

Perspective: We believe this case is important for the following reasons: (1) the ECG is classic and this finding alone warrants consideration for apical HCM; (2) the parasternal long-axis 2D echo demonstration of visualizing the LV apex is classic for apical HCM and should be recognized; (3) the ECG, nuclear SPECT, off-axis 2D echo, and CMR correlate well in support of this diagnosis and emphasize the importance of off-axis imaging using echo; (4) color flow Doppler and color M-mode clearly demonstrate an apically located diastolic gradient. The authors believe that this finding, in combination with microvascular ischemia (as shown in COTW 11-04), likely contributed to the eventual development of the apical aneurysm; and (5) if the CMR had been performed initially, the echo exam and nuclear scan may have been avoided, thus saving thousands of dollars (and time).

References:

1. Kitaoka H, Doi Y, Casey SA, Hitomi N, Furuno T, Maron BJ. Comparison of prevalence of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Japan and the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2003 Nov 15;92(10):1183-6.

2. Matsubara K, Nakamura T, Kuribayashi T, Azuma A, Nakagawa M. Sustained cavity obliteration and apical aneurysm formation in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2003; 42: 288-295.

3. Maron MS, Finley JJ, Bos JM, Hauser TH, Manning WJ, Haas TS, Lesser JR, Udelson JE, Ackerman MJ, Maron BJ. Prevalence, clinical significance, and natural history of left ventricular apical aneurysms in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.Circulation. 2008 Oct 7;118(15):1541-9. Epub 2008 Sep 22

4. T. Nakamura, K. Matsubara, K. Furukawa, A. Azuma, H. Sugihara, H. Katsume and M. Nakagawa, Diastolic paradoxic jet flow in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evidence of concealed apical asynergy with cavity obliteration, J Am Coll Cardiol 19 (1992), pp. 516-524.

5. Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, Rakowski P, Parker TG, Wigle ED, Rakowski H. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Feb 20;39(4):638-45.

6. Gebker R, Neuss M, Paetsch I, Nagel E. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Progressive myocardial fibrosis in a patient with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2006 Aug 1;114(5):e75-6.

COTW handling editor: Vikas K. Rathi, MD