Case from: Lauren Lapointe-Shaw, MDa, *, Jonathan Afilalo, MD b, Lawrence Rudski, MD, FASEb

Institute: a- Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, b- Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Clinical history: A 49 year-old male presented with a 10-day history of worsening shortness of breath, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and orthopnea. Examination revealed pulmonary crackles and a prominent systolic murmur best heard at the apex. Frontal bossing, large hands and a very deep voice were also noted. The electrocardiogram showed high voltages consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy and a chest x-ray confirmed the diagnosis of cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

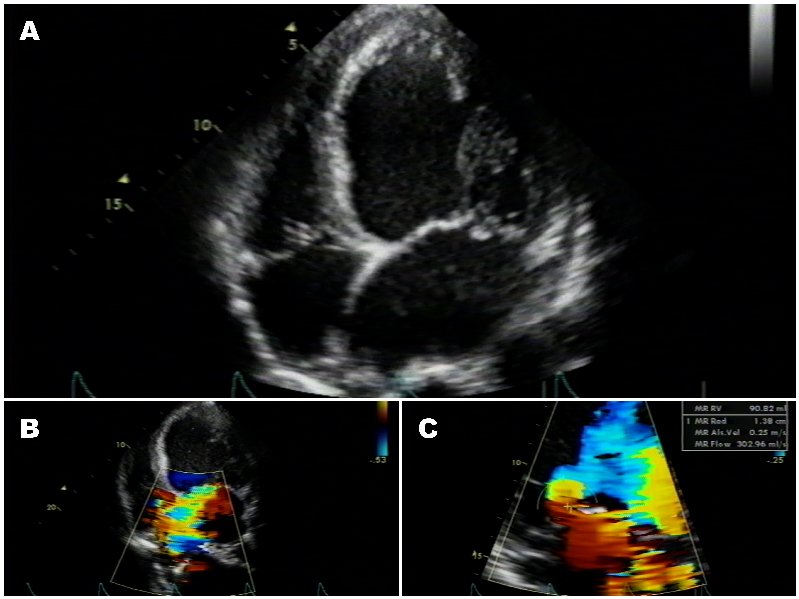

A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and demonstrated severe mitral regurgitation with an effective orifice area of 0.63 cm2, a vena contracta of 8 mm, and a flail middle segment of the posterior mitral leaflet (figure 1). The left ventricle was severely dilated with an end diastolic dimension of 80 mm and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 26% by biplane Simpson’s method. The left atrium was moderately dilated. Right-sided chambers were normal and the right ventricular systolic pressure was estimated at 42 mmHg. The anatomic findings were confirmed by transesophageal echocardiography. Coronary arteriogram showed normal left and right coronary arteries.

(A) Apical 4-chamber view showing a dilated left ventricle and markedly enlarged left atrium with preserved left ventricular wall thickness, (B) Apical 4-chamber view with color Doppler showing severe postero-medially directed mitral regurgitation, (C) color Doppler showing an effective regurgitant area calculated at 0.63 cm2.

Laboratory investigations confirmed the diagnosis of acromegaly: IGF-1 and growth hormone levels were elevated and magnetic resonance imaging of the sella turcica showed a small left-sided pituitary adenoma as the possible source of hypersecretion. The pituitary adenoma was not amenable to surgical resection.

Two treatment options were considered at this point: surgically correcting the mitral regurgitation with a mitral valve repair, accepting a high operative risk in light of the severely depressed left ventricular function. The alternative was pharmacologically correcting the acromegaly with somatostatin therapy, anticipating that this therapy would improve cardiac function and reduce the operative risk of the subsequent mitral valve repair. This second option was contingent upon the viability of the patient’s myocardium.

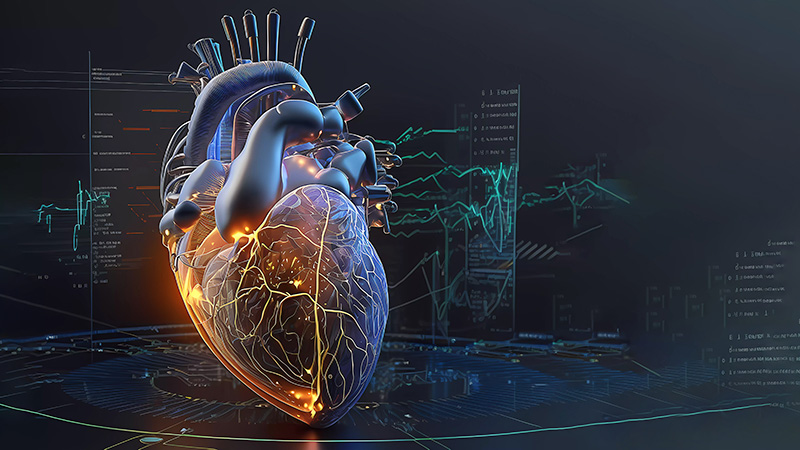

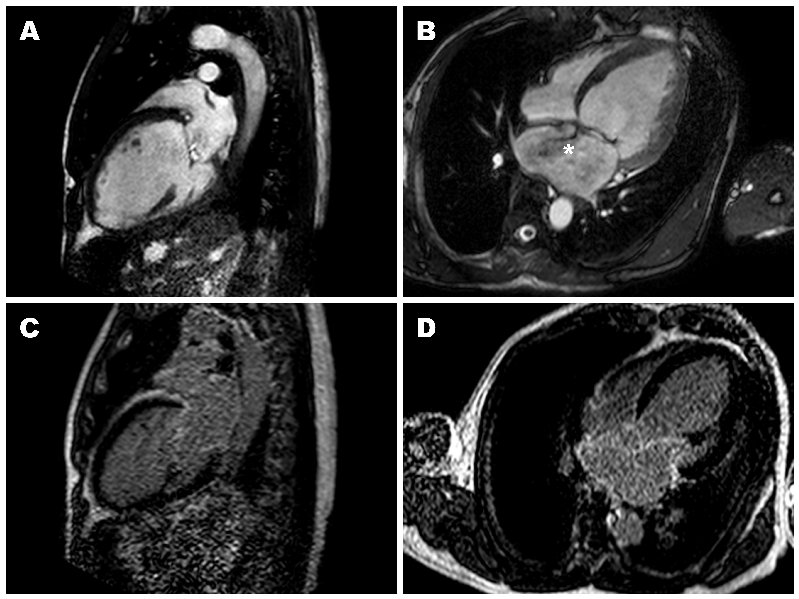

CMR Findings: To determine whether there was significant viability, a cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was performed. This was done with a 1T scanner with steady-state free precession cine sequences, first-pass gadolinium perfusion sequences, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences (Movie 1, 2, 3). CMR showed an LVEF of 19%, diffuse hypokinesis of both ventricles, an elevated left ventricular mass of 145 g/m2, an increased end-diastolic volume of 519 mL and end-systolic volume of 390 mL. There were no segments with reduced first-pass gadolinium perfusion or LGE, suggesting viable myocardium without significant fibrosis (figure 2).

Movie 1: 4 chamber cine CMR demonstrating severe anteriorly directed severe eccentric mitral regugitant jet.

Movie 2: Short axis cine CMR demonstrating poor coaptation of the mitral leaflets with large effective regugitant orifice area.

Movie 3: 2 chamber cine CMR

Figure 2: (A,B) 2- and 4-chamber steady-state free precession cine sequences showing a markedly dilated left ventricle as well as a dark signal void proximal to the mitral valve in systole which represents the mitral regurgitation jet, the * in panel B clearly shows that the mitral regurgitation jet is directed postero-medially, (C,D) 2- and 4-chamber late gadolinium enhancement sequences showing a lack of delayed enhancement and therefore viability in all segments.

Conclusion:

As a result, the treating team decided to pursue the second treatment option, initiating somatostatin therapy and postponing cardiac surgery.

A dual chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was placed for primary prevention, as well as for brief runs of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on telemetry. The patient was treated with somatostatin, enalapril, carvedilol, digoxin and furosemide. After 3 months of treatment, growth hormone levels had normalized and a repeat transthoracic echocardiogram showed improvement in LVEF to 32% and left ventricular end-diastolic dimension to 72 mm (from 80 mm), despite persistent severe mitral regurgitation with flail P2. After 9 months of treatment, there was further improvement in LVEF to 42% and left ventricular end-diastolic dimension to 65 mm. In addition, the effective orifice area had decreased to 0.34 cm2.

After 11 months of treatment, the patient underwent an elective mitral valve repair with resection of P2 and implantation of a Physio # 32 mitral annuloplasty ring. His post-operative course was uncomplicated and he was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. A pre-discharge echocardiogram showed a well-functioning annuloplasty ring with trace mitral regurgitation and an LVEF of 45-50%. The patient was seen in clinic 6 months after his surgery and reported excellent functional capacity (NYHA I), a return to work, and no residual symptoms. He continues to take suppressive somatostatin therapy as well as enalapril and carvedilol.

Perspective:

Although ventricular hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis have been described in an autopsy study of acromegalic hearts(5), the presence of fibrosis has recently been challenged by a CMR study of 14 acromegalic patients (6). In this study, hypertrophy was present in 72% but LGE was present in 0%. Therefore, the absence of LGE in our case and in this CMR study may explain the favorable response to medical therapy seen here. CMR has been used to predict response to therapy in other conditions, as in response to revascularization in patients with severe coronary artery disease(7;8), or response to enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry’s disease(9). There are no data establishing the role of LGE in the prognosis of, or timing of surgery in patients with organic mitral regurgitation, however.

While somatostatin therapy has previously been shown to improve cardiac function and reduce ventricular mass in acromegalic cardiomyopathy(10), the use of CMR to detect viability and guide this treatment decision has never been described. Furthermore, medical therapy is rarely successful in the context of a flail mitral valve which is associated with rapid deterioration rather than improvement in cardiac function and dimensions.

Therefore, our case illustrates that the cardiomyopathy associated with acromegaly may cause significant left ventricular systolic dysfunction and mitral regurgitation, and that treatment of the acromegaly should be considered prior to referral for mitral valve repair. The decision to delay valve surgery should be accompanied by close clinical follow-up, and may be guided by the finding of myocardial viability on CMR.

References:

- Lombardi G, Galdiero M, Auriemma RS, Pivonello R, Colao A. Acromegaly and the cardiovascular system. Neuroendocrinology 2006;83(3-4):211-7.

- Damjanovic SS, Neskovic AN, Petakov MS, Popovic V, Vujisic B, Petrovic M, et al. High output heart failure in patients with newly diagnosed acromegaly. Am J Med 2002 Jun 1;112(8):610-6.

- Bihan H, Espinosa C, Valdes-Socin H, Salenave S, Young J, Levasseur S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with acromegaly and congestive heart failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004 Nov;89(11):5308-13.

- Pereira AM, van Thiel SW, Lindner JR, Roelfsema F, van der Wall EE, Morreau H, et al. Increased prevalence of regurgitant valvular heart disease in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004 Jan;89(1):71-5.

- Lie JT. Pathology of the heart in acromegaly: anatomic findings in 27 autopsied patients. Am Heart J 1980 Jul;100(1):41-52.

- Bogazzi F, Lombardi M, Strata E, Aquaro G, Di B, V, Cosci C, et al. High prevalence of cardiac hypertophy without detectable signs of fibrosis in patients with untreated active acromegaly: an in vivo study using magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008 Mar;68(3):361-8.

- Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, Chen EL, Parker MA, Simonetti O, et al. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2000 Nov 16;343(20):1445-53.

- Selvanayagam JB, Kardos A, Francis JM, Wiesmann F, Petersen SE, Taggart DP, et al. Value of delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in predicting myocardial viability after surgical revascularization. Circulation 2004 Sep 21;110(12):1535-41.

- Weidemann F, Niemann M, Breunig F, Herrmann S, Beer M, Stork S, et al. Long-term effects of enzyme replacement therapy on fabry cardiomyopathy: evidence for a better outcome with early treatment. Circulation 2009 Feb 3;119(4):524-9.

- Maison P, Tropeano AI, quin-Mavier I, Giustina A, Chanson P. Impact of somatostatin analogs on the heart in acromegaly: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007 May;92(5):1743-7.

Submit your case here

COTW handling editor: Vikas K. Rathi, MD

Have your say: What do you think? Latest posts on this topic from the forum